IS Families/IS200-IS605 family: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (45 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

=== | == Historical == | ||

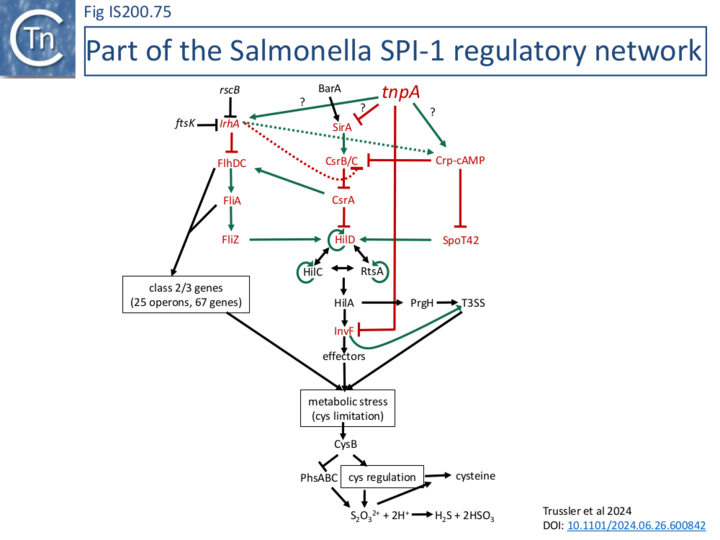

One of the founding members of this group, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], was identified in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|Salmonella typhimurium]]'' <ref name=":11">{{#pmid:6313217}}</ref> as a mutation in ''hisD'' ([https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/X56834.1 hisD984]) which mapped as a point mutation but which did not revert and was polar on the downstream ''hisC'' gene (see <ref name=":3">{{#pmid:15179601}}</ref>). [[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|''S. typhimurium'' LT2]] was found to contain six [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] copies and the IS was unique to ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|Salmonella]]'' <ref name=":15">{{#pmid:6315530}}</ref>. Further studies <ref name=":13">{{#pmid:3009825}}</ref> showed that the IS did not carry repeated sequences, either '''direct''' or '''inverted''', at its ends, and that removal of 50 bp at the transposase proximal end (which includes a structure resembling a transcription terminator) removed the strong transcriptional block. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] elements from ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|S. typhimurium]]'' and ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|S. abortusovis]]'' revealed a highly conserved structure of 707–708 bp with a single open-reading-frame potentially encoding a 151 aa peptide and a putative upstream [[wikipedia:Ribosome-binding_site|ribosome-binding-site]] <ref name=":17">{{#pmid:9060429}}</ref>. | |||

It has been suggested that a combination of inefficient transcription, protection from impinging transcription by a transcriptional terminator, and repression of translation by a stem-loop mRNA structure. All contribute to tight repression of transposase synthesis <ref name=":3" />. However, although [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] seems to be relatively inactive in transposition <ref>{{#pmid:2546038}}</ref>, it is involved in chromosome arrangements in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|S. typhimurium]]'' by recombination between copies <ref>{{#pmid:8601470}}</ref>. | |||

A second group of “founding” members of this family was, arguably, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''] from the [[wikipedia:Thermophile|thermophilic bacterium PS3]] <ref name=":16">{{#pmid:7557457}}</ref>, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS891 IS''891''] from [[wikipedia:Anabaena|''Anabaena'' sp]]. M-131 <ref name=":8">{{#pmid:2553665}}</ref> and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1136 IS''1136''] from ''[[wikipedia:Saccharopolyspora_erythraea|Saccharopolyspora erythraea]]'' <ref>{{#pmid:8386127}}</ref>. The “transposases” of both elements were observed to be associated in a single IS, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''], from the gastric pathogen ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|Helicobacter pylori]]'' <ref name=":12">{{#pmid:9858724}}</ref>. It was identified in many independent isolates of ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' and is now considered to be a central member which defines this large family. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] was shown to possess unique, not inverted repeat, ends; did not duplicate target sequences during transposition; and inserted with its left ([https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200'']-homolog) end abutting 5'-'''TTTAA''' or 5'-'''TTTAAC''' target sequences <ref name=":12" />. Additionally, a second derivative, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS606 IS''606''], with only 25% amino acid identity in the two proteins (''orfA'' and ''orfB'') was also identified in many of the ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' isolates including some which were devoid of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605'']. The Berg lab also identified another ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' IS, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS607 IS''607''] <ref name=":5">{{#pmid:10986230}}</ref> which carried a similar [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like orf (''orfB'') but with another upstream orf with similarities to that of the mycobacterial [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1535 IS''1535''] <ref>{{#pmid:10220167}}</ref> annotated as a resolvase due the presence of a site-specific [[wikipedia:Site-specific_recombination|serine recombinase]] motif. Another [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] derivative, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISHp608 IS''Hp608''], which appeared widely distributed in [[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|''H. pylori'']] was shown to transpose in ''[[wikipedia:Escherichia_coli|E. coli]]'', required only ''orfA'' to transpose and inserted downstream from a 5’-'''TTAC''' target sequence <ref name=":6">{{#pmid:11807059}}</ref>. | |||

== General == | |||

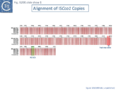

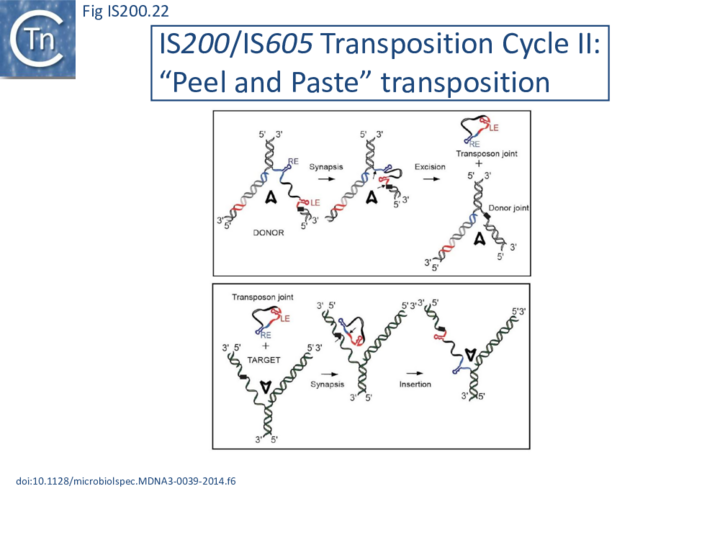

[[ | The IS''200''/IS''605'' family members transpose using obligatory '''s'''ingle '''s'''trand(ss) DNA intermediates <ref name=":22">{{#pmid:26104715}}</ref> by a mechanism called “'''peel and paste'''”. They differ fundamentally in the organization from classical IS. They have sub-terminal palindromic structures rather than terminal '''IRs''' ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]]) and insert 3’ to specific AT-rich tetra- or penta-nucleotides without duplicating the target site. | ||

[[File:FigIS200 605 1.png|alt=|center|thumb|640x640px|'''Fig. IS200.1.''' Genetic organization. '''Left''' (LE) and '''right''' (RE) ends carrying the subterminal hairpin (HP) are presented as red and blue boxes, respectively. Left and right cleavage sites (CL and CR) are presented as black and blue boxes respectively, where the black box also represents element-specific tetra-/pentanucleotide target site (TS). The cleavage positions are indicated by small vertical arrows. Gray arrows: ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' open reading frames (orfs); '''(i)''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group with ''tnpA'' alone; '''(ii)''' to '''(iv)''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group with ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' in different configurations; '''(v)''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''] group with ''tnpB'' alone.]] | |||

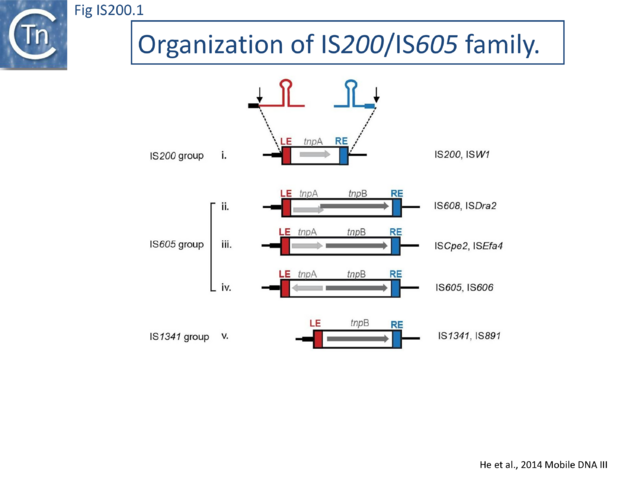

The transposase, TnpA, is a member of the HUH enzyme superfamily ([[wikipedia:Relaxase|Relaxases]], Rep proteins of RCR plasmids/ss phages, bacterial and eukaryotic transposases of [[IS Families/IS91-ISCR families|IS''91''/IS''CR'' and Helitrons]]<ref>{{#pmid:26350323}}</ref><ref name=":1">{{#pmid:23832240}}</ref>)([[:File:FigIS200 605 2rev.png|Fig. IS200.2]]) which all catalyze cleavage and rejoining of ssDNA substrates. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 2rev.png|alt=|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.2.''' The IS''200''/IS''605'' family transposases are “minimal” and the smallest transposases presently know. They include the HUH and Y motifs and use Y as the attacking nucleophile to generate 5’ phosphotyrosine covalent intermediates. HUH transposases from other transposon families include additional domains.]] | |||

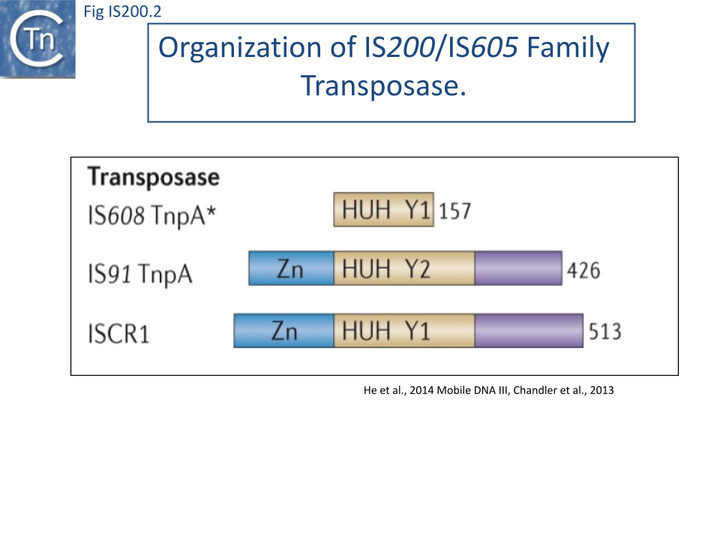

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], the founding member ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.3]]), was identified 30 years ago in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|Salmonella typhimurium]] <ref name=":11" />'' but there has been renewed interest for these elements since the identification of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group in ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|Helicobacter pylori]] <ref name=":12" />''<ref>{{#pmid:9631304}}</ref><ref name=":6" />. Studies of two elements of this group, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] from ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] from the radiation resistant ''[[wikipedia:Deinococcus_radiodurans|Deinococcus radiodurans]]'', have provided a detailed picture of their mobility <ref name=":23">{{#pmid:16209952}}</ref><ref name=":24">{{#pmid:16163392}}</ref><ref name=":7">{{#pmid:18280236}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{#pmid:18243097}}</ref><ref name=":32">{{#pmid:20090938}}</ref><ref name=":25">{{#pmid:20691900}}</ref><ref name=":9">{{#pmid:20890269}}</ref>. | |||

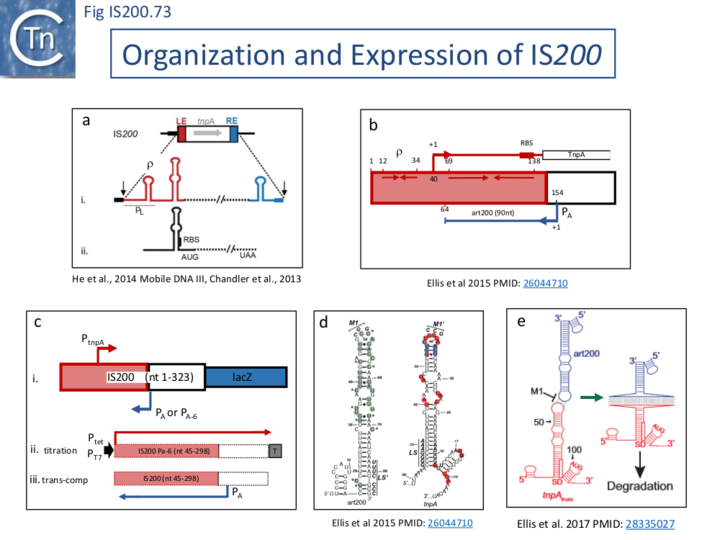

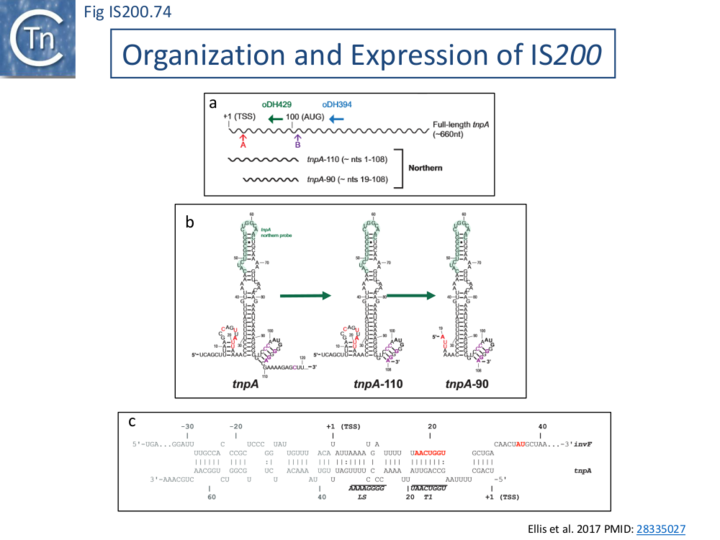

[[File:FigIS200 605 3.png|alt=|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.3.''' '''Top''': [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] Secondary structures in '''LE ('''red) and '''RE''' (blue), promoter (pL), [[wikipedia:Ribosome-binding_site|'''R'''ibosome '''B'''inding '''S'''ite]] ('''RBS'''), and ''tnpA'' start and stop codons (AUG and UAA) are indicated. '''(i)''' DNA top strand with perfect palindromes at LE and RE in red and blue, interior stem-loop in black, '''(ii)''' RNA stem-loop structure in transcript originated from pL. '''Bottom:''' ''tnpA'' transcription originates at about nt 40, but promoter elements are not defined; the ‘left end’ contains two internal inverted repeats (opposing arrows), one of which acts as a transcription terminator (nts 12–34). The second, (nts 69–138) in the 5’UTR of the tnpA mRNA sequesters the [[wikipedia:Shine-Dalgarno_sequence|Shine-Dalgarno]] sequence. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' also expresses a 90 nt sRNA (asRNA, art200, or STnc490) perfectly complementary to the 5’UTR and the first three codons of ''tnpA''. The transcription start site and 3’ end for art200 in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' (derived from RNA-Seq experiments) are shown, but promoter elements were not previously defined.]] | |||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], the | == Distribution and Organization == | ||

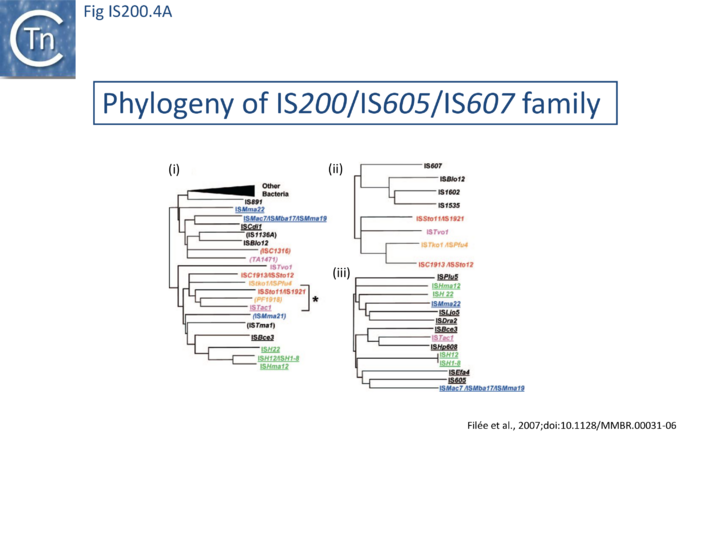

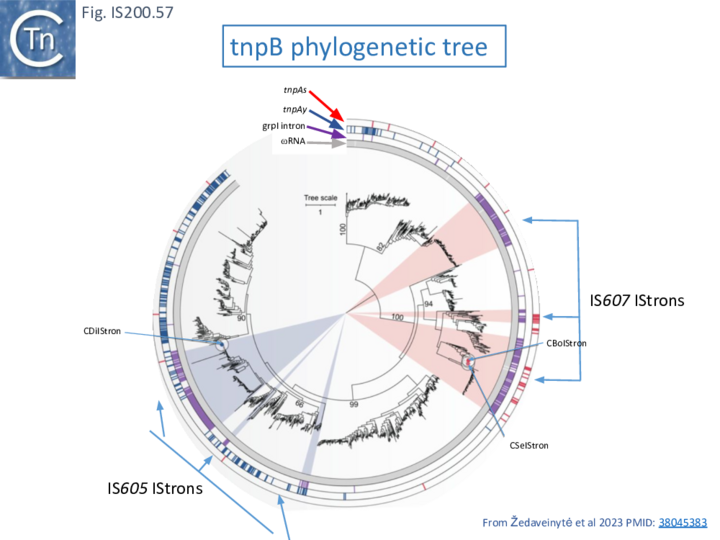

The family is widely distributed in prokaryotes with more than 153 distinct members (89 are distributed over 45 genera and 61 species of [[wikipedia:Bacteria|bacteria]], and 64 are from [[wikipedia:Archaea|archaea]]). It is divided into three major groups based on the presence or absence and on the configuration of two genes: the transposase ''tnpA'' (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/cog/COG1943/), sufficient to promote IS mobility ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro'' and ''tnpB'' (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/cog/COG0675/) ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]]) initially of unknown function and not required for transposition activity but now known to de an RNA-guide endonuclease (see [http://tnpedia.fcav.unesp.br/index.php/IS_Families/IS200-IS605_family#TnpB TnpB below]) . These groups are: [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']. TnpB is also present in another [[IS Families/IS607 family|IS family, IS''607'']], which uses a [[wikipedia:Site-specific_recombination|serine-recombinase]] as a transposase. In the phylogeny of this group ([[:File:FigIS200 605 4A.png|Fig. IS200.4A]]) of IS, both ''tnpB'' and ''tnpA'' of bacterial or archaeal origin are intercalated, suggesting some degree of horizontal transfer between these two groups of organisms<ref name=":2">{{#pmid:17347521}}</ref>. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 4A.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.4.''' '''(i)''' Phylogeny-based on ''tnpB'' of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200'']/[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605'']/[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS607 IS''607''] family. '''(ii)''' Phylogeny-based on ''tnpA'' of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS607 IS''607''] family ([[wikipedia:Site-specific_recombination|serine recombinase]]). '''(iii)''' Phylogeny-based on ''tnpA'' of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] family (HUH transposase). IS''608'' elements are underlined, single ''orfB'' elements are indicated between brackets, and the asterisk indicates the mosaic construction of the elements of this family (see the text). The various Archaea have been color-coded as follows for clarity: [[wikipedia:Sulfolobales|Sulfolobales]], red; [[wikipedia:Thermoplasmatales|Thermoplasmatales]], magenta; [[wikipedia:Halophile|halophiles]], green; [[wikipedia:Methanogen|methanogens]], blue; “other,” orange. Bacteria are indicated in black.]] | |||

Isolated copies of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200'']-like ''tnpA'' can be identified in both bacteria and archaea<ref name=":2" />. Full length copies of IS''605''-like elements are also found in bacteria and several archaea and all have corresponding MITEs ('''M'''iniature '''I'''nverted repeat '''T'''ransposable '''E'''lements) derivatives in their host genomes. | |||

====The IS''200'' group==== | |||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group members encode only ''tnpA'', and are present in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and certain archaea<ref name=":3" /><ref>{{#pmid:10418150}}</ref> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] and [[:File:FigIS200 605 3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]). Alignment of TnpA from various members shows that they are highly conserved but may carry short C-terminal tails of variable length and sequence. Among approximately 400 entries in ISfinder (December 2023), about 50 examples IS''200''-like derivatives. | |||

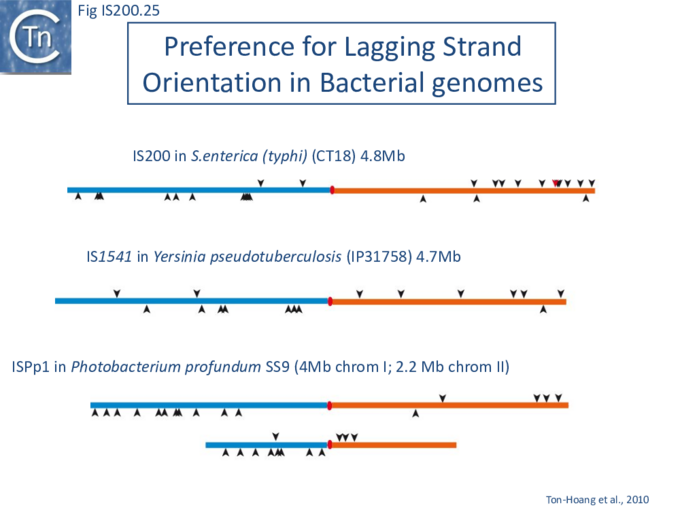

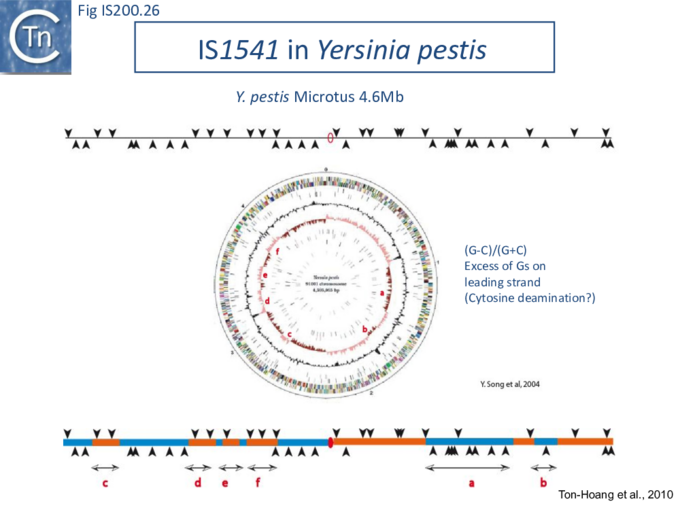

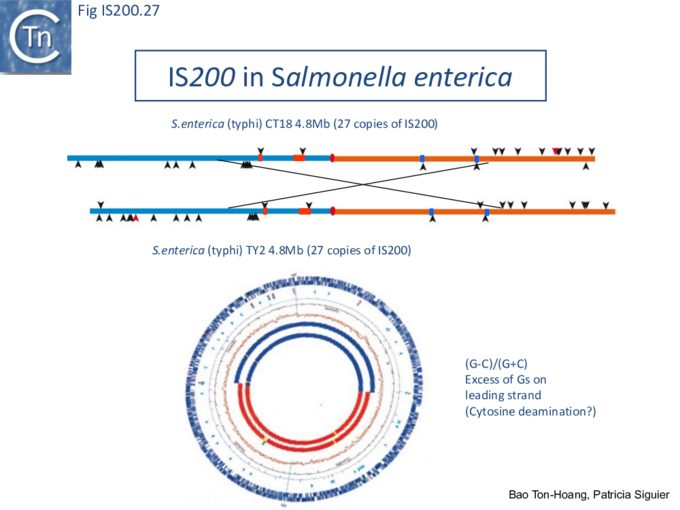

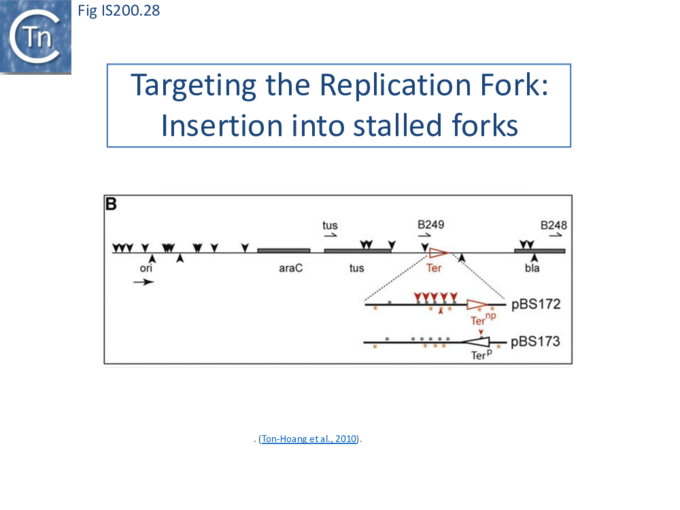

They can occur in relatively high copy number (e.g. >50 copies of IS''1541'' in ''[[wikipedia:Yersinia_pestis|Yersinia pestis]]'') and are among the smallest known autonomous IS with lengths generally between 600-700 pb. Some members such as [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISW1 IS''W1''] (from ''[[wikipedia:Wolbachia|Wolbachia]]'' sp.) or [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISPrp13 IS''Prp13''] (from ''[[wikipedia:Photobacterium_profundum|Photobacterium profundum]]'') are even shorter. | |||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] was initially identified as an insertion mutation in the ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella_enterica_subsp._enterica|Salmonella typhimurium]]'' histidine operon <ref name=":11" />. It is abundant in different ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' strains and has now also been identified in a variety of other enterobacteria such as ''[[wikipedia:Escherichia|Escherichia]]'', ''[[wikipedia:Shigella|Shigella]]'' and ''[[wikipedia:Yersinia|Yersinia]]''. | |||

Different enterobacterial [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] copies have almost identical lengths of between 707 and 711bp. Analysis of the ECOR (''[[wikipedia:Escherichia_coli|E. coli]]'') and SARA (''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonellae]]'') collections showed that the level of sequence divergence between [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] copies from these hosts is equivalent to that observed for chromosomally encoded genes from the same taxa<ref>{{#pmid:8253675}}</ref><ref>{{#pmid:8384142}}</ref>. This suggests that [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] was present in the common ancestor of ''[[wikipedia:Escherichia_coli|E. coli]]'' and ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonellae]]''. | |||

In spite of their abundance, an enigma of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] behavior is its poor contribution to spontaneous mutation in its original ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' host: only very rare insertion events have been documented <ref name=":3" />. One reason for these rare insertions could be due to poor expression of the TnpA<sub>IS''200''</sub> gene from a weak promoter pL identified at the left IS end (LE)<ref name=":13" /><ref name=":17" /> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]). | |||

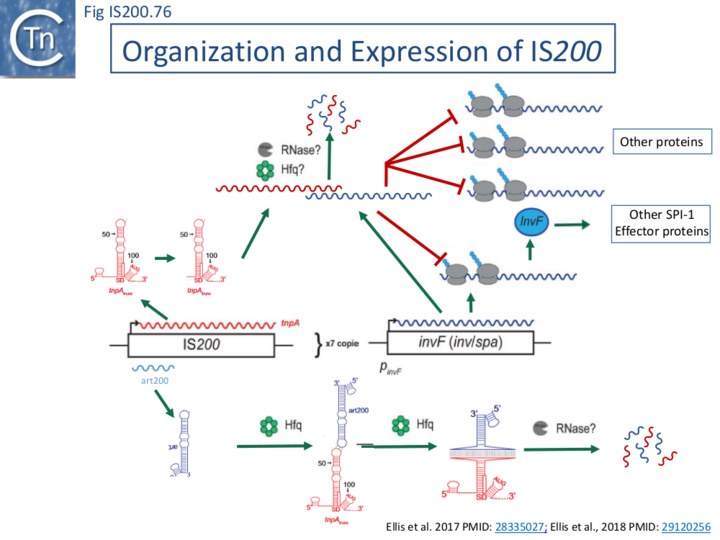

Besides the characteristic major subterminal palindromes <ref name=":13" /> presumed binding sites of the transposase at both '''LE''' and the right end ('''RE''') (Substrate recognition), [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] carries also a potential supplementary interior stem-loop structure ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]). These two structures play a role in regulating [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] gene expression. The first (perfect palindrome at LE; nts 12–34) overlaps the TnpA<sub>IS''200''</sub> promoter pL, can act as a bi-directional transcription terminator upstream of TnpA<sub>IS''200''</sub> and terminates up to 80% of transcripts<ref name=":4">{{#pmid:10471738}}</ref> ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]). The second (interior stem-loop; nts 69–138) ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]), at the RNA level, can repress mRNA translation by sequestration of the [[wikipedia:Ribosome-binding_site|'''R'''ibosome '''B'''inding '''S'''ite (RBS)]] ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]). Experimental data suggested that the stem-loop is formed ''in vivo'' and its removal by mutagenesis caused up to a 10 fold increase in protein production<ref name=":4" />. Recent deep sequencing analysis revealed another aspect in post-transcriptional regulation of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] expression: A small anti-sense RNA ('''asRNA''') [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] transposase expression ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]) was identified as a substrate of [[wikipedia:Hfq_protein|Hfq]], an RNA chaperone involved in post-transcriptional regulation in numerous bacteria<ref>{{#pmid:18725932}}</ref>. Interestingly, asRNA and [[wikipedia:Hfq_protein|Hfq]] independently inhibit [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] transposase expression: knock-out of both components resulted in a synergistic increase in transposase expression. Moreover, footprint data showed that [[wikipedia:Hfq_protein|Hfq]] binds directly to the 5’ part of the transposase transcript and blocks access to the [[wikipedia:Ribosome-binding_site|RBS]]<ref>{{#pmid:26044710}}</ref>. | |||

[[ | |||

In spite of its very low transposition activity, an increase in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] copy number was observed during strain storage in stab cultures<ref name=":11" /><ref name=":15" />. However, the factors triggering this activity remain unknown<ref name=":3" /> . Transient high transposase expression leading to a burst of transposition was proposed to explain the observed high [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] (>20) copy number in various hosts and in stab cultures <ref name=":11" />. | |||

Although regulatory structures similar to that observed in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] ([[:File:Fig. IS200.3.png|Fig. IS200.3]]) were predicted in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1541 IS''1541''], another member of this group with 85% identity to [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], this element can be detected in higher copy number (> 50) in ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' and ''[[wikipedia:Yersinia|Yersinia]]'' genomes. However, no detailed analysis of its transposition is available and since no de novo insertions have been experimentally documented and chromosomal copies appear stable in ''[[wikipedia:Yersinia_pestis|Y. pestis]]''<ref>{{#pmid:9422611}}</ref>, it remains possible that [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1541 IS''1541''] also behaves like [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200'']. | |||

However, the regulatory structures are not systematically present in other [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group members and understanding of the control of transposase synthesis requires further study. | |||

====The IS''605'' group==== | |||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group members are generally longer (1.6-1.8 kb) due to the presence of a second ''orf'', ''tnpB'' in addition to ''tnpA''. Alignment of TnpA copies from this group indicated that although they do not form a separate clade from the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group TnpA, they generally carry the short C-terminal tail. The ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' orfs exhibit various configurations with respect to each other. They may be divergent ([[:File:Fig. IS200.1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] '''i''' top: e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS606 IS''606'']) or expressed in the same direction with ''tnpA'' upstream of ''tnpB''. In these latter cases, the orfs may be partially overlapping ([[:File:Fig. IS200.1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] '''ii'''; e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2'']) or separate [[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] '''iii'''; e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSCpe2 IS''SCpe2''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISEfa4 IS''Efa4'']). ''tnpB'' is also sometimes associated with another transposase, a member of the S-transposases (e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS607 IS''607'']''<ref name=":5" />''<ref name=":45">{{#pmid:24195768}}</ref>, see <ref name=":22" />. TnpB was not required for transposition of either [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] or [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2'']. | |||

=== | Three related IS, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS606 IS''606''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] ([[:File:Fig. IS200.1.png|Fig. IS200.1]]) have been identified in numerous strains of the gastric pathogen ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|Helicobacter pylori]] <ref name=":12" /><ref name=":6" />'' . [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] is involved in genomic rearrangements in various ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' isolates<ref>{{#pmid:9789049}}</ref>. | ||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name= | |||

The ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|H. pylori]]'' elements transpose in ''[[wikipedia:Escherichia_coli|E. coli]]'' at detectable frequencies in a standard "mating-out" assay using a derivative of the conjugative [[wikipedia:Fertility_factor_(bacteria)|F plasmid]] as a target <ref name=":12" /><ref name=":6" />. | |||

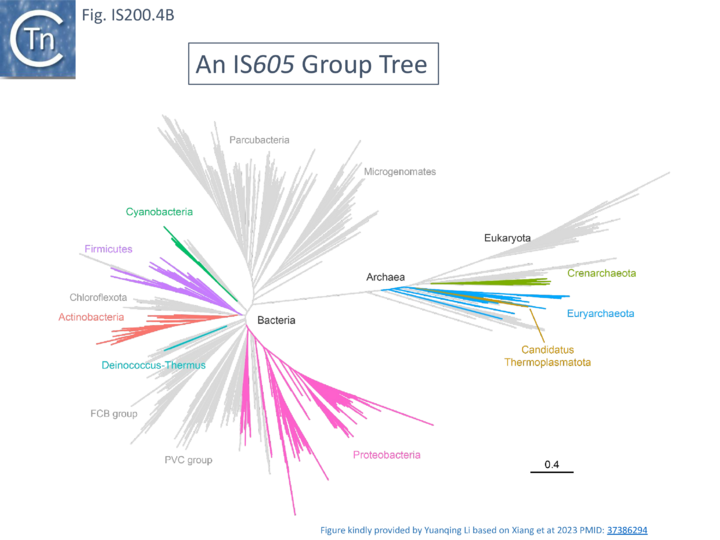

[[File:FigIS200 605 4B.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.4B. An IS''605'' Group Tree.''' Distribution based on Xiang et al <ref name=":14">{{#pmid:37386294}}</ref>. The different colors represent the 8 TnpB clusters identified layered onto the tree of life (A new view of the tree of life <ref name=":10">{{#pmid:27572647}}</ref>. Figure kindly provided by Yuanqing Li.]] | |||

The two best characterized members of this family are [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and the closely related [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] from ''[[wikipedia:Deinococcus_radiodurans|Deinococcus radiodurans]]''. Both have overlapping ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' genes ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] '''ii'''). Like other family members, insertion is sequence-specific: [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] inserts in a specific orientation with its left end 3’ to the tetranucleotide TTAC both ''in vivo'' and ''in vitro<ref name=":6" />'' while [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] inserts 3’ to the pentanucleotide TTGAT<ref>{{#pmid:14676423}}</ref>. Interestingly [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] transposition in its highly radiation resistant Deinococcal host is strongly induced by irradiation<ref name=":262">{{#pmid:17006450}}</ref> (Single strand DNA ''in vivo''). Their detailed transposition pathway has been deciphered by a combination of ''in vivo'' studies and ''in vitro'' biochemical and structural approaches ([[IS Families/IS200 IS605 family#Mechanism of IS200.2FIS605 single strand DNA transposition|Mechanism of IS''200''/IS''605'' single strand DNA transposition]]). | |||

A more detailed and recent analysis of the distribution of 107 IS''605'' group elements in ISfinder is shown in [[:File:FigIS200 605 4B.png|Fig. IS200.4B]] <ref name=":14" />. The tree, based on TnpB sequences could be divided into 8 clusters which are overlaid onto the universal tree described by Hug et al., 2016 <ref name=":10" />. | |||

====The IS''1341'' group==== | |||

Elements of the third group, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''], are devoid of ''tnpA'' and carry only ''tnpB'' ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]] '''v'''). The IS occurs in three copies in [[wikipedia:Thermophile|Thermophilic bacterium]] PS3 <ref name=":16" />. Multiple presumed full-length elements (including ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'') and closely related copies have been identified in other bacteria such as ''[[wikipedia:Geobacillus|Geobacillus]]''. On the other hand, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS891 IS''891''] from the cyanobacterium ''[[wikipedia:Anabaena|Anabaena]]'' is present in multiple copies on the chromosome and is thought to be mobile since a copy was observed to have inserted into a plasmid introduced in the strain<ref name=":8" />. | |||

Another isolated ''tnpB''-related gene, ''[https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q50HS5 gipA]'', present in the ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' Gifsy-1 prophage may be a virulence factor since a ''gipA'' null mutation compromised ''[[wikipedia:Salmonella|Salmonella]]'' survival in a Peyer's patch assay <ref>{{#pmid:10913072}}</ref>. While no mobility function has been suggested for ''gipA'', it is indeed bordered by structures characteristic of IS''200''/IS''605'' family ends and closely related to ''[[wikipedia:Escherichia_coli|E. coli]]'' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISEc42 IS''Ec42'']. | |||

[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] | In spite of their presence in multiple copies, it is still unclear whether [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''] group members are autonomous IS or products of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group degradation and require TnpA supplied from a related IS in the same cell for transposition. | ||

====IS decay==== | |||

Circumstantial evidence based on analysis of the [https://isfinder.biotoul.fr/ ISfinder database] suggests that IS carrying both ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' genes may be unstable. Thus, although members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group are often present in high copy number in their host genomes, intact full-length [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group members are invariably found in low copy number ([https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=WHAtfqcAAAAJ&hl=pt-BR P. Siguier], unpublished) (See also [[IS Families/IS200-IS605 family#TnpB|TnpB]]). On the other hand, various truncated [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group derivatives appear quite frequently ([[:File:IS200.slide.show.1.A.png|Fig. IS200.slide show 1]], [[:File:IS200.slide.show.2.A.png|slide show 2]] ,[[:File:IS200.slide.show.3.A.png|slide show 3]], [[:File:IS200.slide.show.4.A.png|slide show 4]], and [[:File:IS200.slide.show.5.A.png|slide show 5]]).<gallery mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.1.A.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 1.''' Decay of ''[[wikipedia:Campylobacter|Campylobacter coli]]'' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''] | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.1.B.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 1.''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''] Insertion Sites and '''LE''' and '''RE''' Cleavage | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.1.C.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 1.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.1.D.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 1.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.1.E.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 1.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''] Copies | |||

</gallery><gallery mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.2.A.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 2.''' Decay of ''[[wikipedia:Cyanothece|Cyanothece]]'' sp. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp14 IS''Cysp14'']''.'' | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.2.B.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 2.''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp13 IS''Cysp13''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp14 IS''Cysp14''] '''LE''' and '''RE''' Cleavage Sites | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.2.C.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 2.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp14 IS''Cysp14''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.2.D.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 2.''' Alignment of ''[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp14 ISCysp14]'' Copies | |||

</gallery><gallery mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.A.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Decay of [[wikipedia:Synechococcus|''Synechococcus'' sp.]] [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.B.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] '''LE''' and '''RE''' Cleavage Sites | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.C.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.D.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.E.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.F.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.3.G.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 3.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] Copies | |||

</gallery><gallery mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.A.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Decay of ''[[wikipedia:Synechococcus_elongatus|Thermosynechococcus elongatus]]'' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.B.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] '''LE''' and '''RE''' Cleavage Sites | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.C.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.D.png| '''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.E.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.F.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] Copies | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.4.G.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 4.''' Alignment of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''] Copies | |||

</gallery><gallery mode="slideshow"> | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.5.A.png| '''Fig. IS200.slide show 5.''' Decay of ''[[wikipedia:Synechococcus_elongatus|T. elongatus]]'' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel3 IS''Tel3''] Towards MICs | |||

File:IS200.slide.show.5.B.png|'''Fig. IS200.slide show 5.''' [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel3 IS''Tel3''] '''LE''' and '''RE''' Cleavage Sites | |||

</gallery>These forms seem to result from successive internal deletions and retain intact '''LE''' and '''RE''' copies. Sometimes, as in the case of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3''] ([[:File:IS200.slide.show.3.A.png|slide show 3]])., orf inactivation appears to have occurred by successive insertion/deletion of short sequences (indels) generating frameshifts and truncated proteins. For some IS (e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCco1 IS''Cco1''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISCysp14 IS''Cysp14''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISSoc3 IS''Soc3'']) degradation can be precisely reconstituted and each successive step validated by the presence of several identical copies ([https://scholar.google.com/citations?user=WHAtfqcAAAAJ&hl=pt-BR P. Siguier], unpublished - [[:File:IS200.slide.show.1.A.png|Fig. IS200.slide show 1]], [[:File:IS200.slide.show.2.A.png|slide show 2]] ,[[:File:IS200.slide.show.3.A.png|slide show 3]], [[:File:IS200.slide.show.4.A.png|slide show 4]], and [[:File:IS200.slide.show.5.A.png|slide show 5]], respectively). This suggests that the degradation process is recent and that these derivatives are likely mobilized by TnpA supplied in trans by autonomous copies in the genome. | |||

Among the approximately 400 IS''200''/IS''605'' family entries in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/index.php ISfinder] (December 2023), there are more than 200 examples of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like derivatives. It was suggested that the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like derivatives might undergo transposition using a resident ''tnpA'' gene to supply a Y1 transposase ''in trans.'' There is some circumstantial evidence for transposition of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like elements. For example, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS891 IS''891''], present in multiple copies in the cyanobacterium ''[[wikipedia:Anabaena|Anabaena]]'' sp. strain M-131 genome <ref name=":8" /> was observed to have inserted into a plasmid which had been introduced into the strain and more recently it has been shown experimentally that [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''] derivatives can be mobilized by a resident ''tnpA'' gene <ref name=":19">{{#pmid:37758954}}</ref> (see [[IS Families/IS200 IS605 family#The IS1341 Conundrum: how do derivatives without their transposase transpose.3F|The IS''1341'' Conundrum]]). This can be followed from a full length IS to the formation of MITES (e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel2 IS''Tel2'']; [[:File:IS200.slide.show.4.A.png|slide show 4]]) and MICs (e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISTel3 IS''Tel3'']; [[:File:IS200.slide.show.5.A.png|slide show 5]]). | |||

====ISC: A group of Elements Related to the IS''605'' Group==== | |||

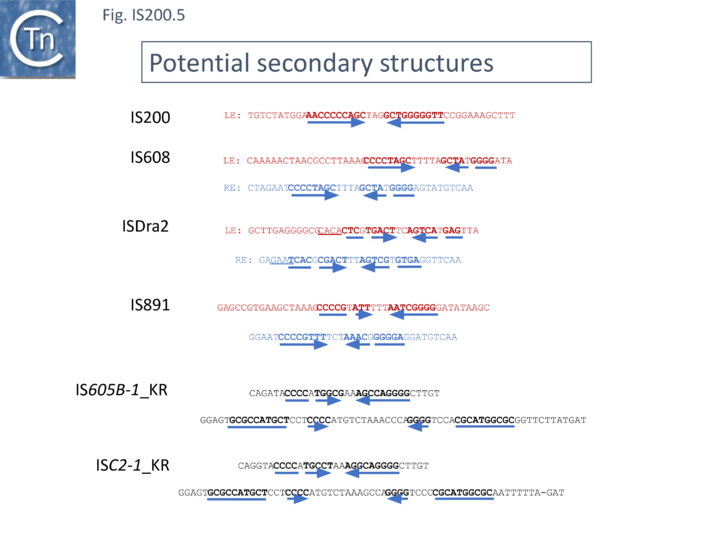

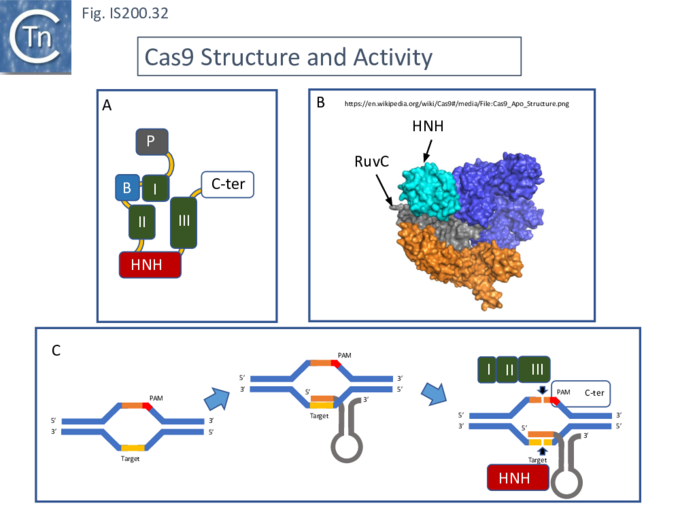

Another group of potential IS of similar organisation, the ISC insertion sequence group, was defined by Kapitonov et al.<ref name=":29">{{#pmid:PMC4810608}}</ref> following identification of [[wikipedia:Cas9|Cas9]] homologues which occur outside the [[wikipedia:CRISPR|CRISPR]] structure, so called “stand-alone” homologues. While related to TnpB, they are more similar to [[wikipedia:Cas9|Cas9]] than to TnpB proteins. These genes were often flanked by short DNA sequences which, like '''LE''' and '''RE''' of the IS''200''/IS''605'' family, were capable of forming secondary structures. Moreover, it was reported that the ends of many ISC derivatives showed significant identity to members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] derivatives identified by these authors in the same study. ([[:File:FigIS200 605 5.png|Fig. IS200.5]]). These structures therefore resemble the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like group. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 5.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.5.''' Potential secondary structures in IS''200''/IS''605''/ISC ends. For the IS''200/''IS''605'' members, the sequences of the left ('''LE''') and right ('''RE''') ends are shown in red and blue respectively. Note that these structures have only been verified for I[https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISHp608 IS''Dra2''] The other sequences are from Kapitonov et al. <ref name=":29" />. The potential secondary structures are indicated by horizontal blue arrows and bold type face.]] | |||

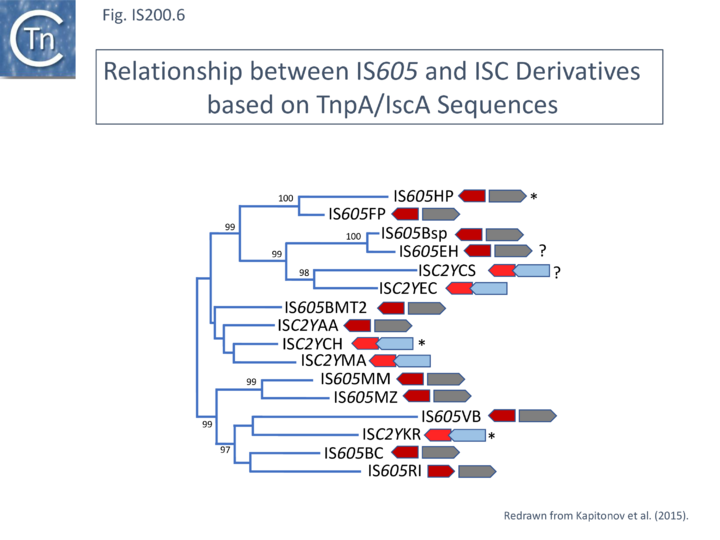

These potential transposable elements were called '''ISC''' (Insertion Sequences Encoding [[wikipedia:Cas9|Cas9]]; not to be confused with [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/TnPedia/index.php/IS_Families/IS91-ISCR_families#ISCR IS''CR'', IS with '''C'''ommon '''R'''egion]). The name IscB was coined for the [[wikipedia:Cas9|Cas9-like]] protein and IscA for an associated potential transposase protein which was identified in a very limited number of cases. Examples of ISC elements with both ''iscA'' and ''iscB'' genes are quite rare. Only 7 cases were identified by Kapitonov et al.,<ref name=":29" /> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 6.png|Fig. IS200.6)]] and only 56 of 2811 ''iscB'' examples observed in a more extensive analysis were accompanied by an ''iscA'' copy <ref name=":30">{{#pmid:34591643}}</ref> . Most ISC identified were [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341'']-like with only the ''iscB'' (''tnpB''-like) gene. These stand-alone IscB copies were identified in multiple copies in a large number of bacterial and archaeal genomes generally in low numbers (<10 copies) although some genomes contained more elevated numbers (e.g. 22 in ''[[wikipedia:Methanosarcina|Methanosarcina lacustris]]''; 25 in ''[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=64178 Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes]'' PCC 7420; 52 in ''[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=363277&lvl=3&lin=f&keep=1&srchmode=1&unlock Ktedonobacter racemifer]'')<ref name=":29" />. | |||

However, in contrast to the observations of Kapitonov et al.,<ref name=":29" /> more wide-ranging studies <ref name=":30" /> identified rare IscB proteins which were not “stand alone” but were associated with [[wikipedia:CRISPR|CRISPR]] arrays (31 examples in a sample of 2811). | |||

A tree of “full-length” elements ([[:File:FigIS200 605 6.png|Fig. IS200.6]]; <ref name=":29" />)(i.e. those with both ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' or ''iscB'' genes) based on TnpA/IscA sequences showed that full length [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] and ISC examples carrying both ''tnpA''/''iscA'' and ''tnpB''/''iscB'' are interleaved. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] is among those family members with divergent ''tnpA'' and ''tnpB'' genes ([[:File:FigIS200 605 1.png|Fig. IS200.1]]) while other family members carry ''tnpA'' upstream of ''tnpB'' (e.g. [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2'']). However, in contrast to all [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605'']-like derivatives, those full length ISC elements included in this tree all have the ''iscA'' gene downstream of and slightly overlapping with ''iscB''. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 6.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.6.''' Phylogenetic tree of Y1 transposases encoded by IS''605'' (TnpA) and IS''C2Y'' (IscA). From Kapitonov et al. <ref name=":29" />. TnpA: RED; IscA: LIGHT RED; TnpB: GREY; IscB: BLUE. The arrowheads indicate the direction of expression. The IS were identified in: '''KR''', ''[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=363277 Ktedonobacter racemifer]'' DSM44963; '''CS''', ''[[wikipedia:Coprobacillus|Coprobacillus]]'' sp. 3_3_56FAA; '''EC''', ''[[wikipedia:Enterococcus|Enterococcus cecorum]]'' DSM 20682 (ATCC 43198); '''AA''', ''[[wikipedia:Anaeromusa_acidaminophila|Anaeromusa acidaminophila]]'' DSM 3853; '''CH''', ''[[wikipedia:Clostridium_novyi|Clostridium. haemolyticum]]'' NCTC 9693; '''MA''', ''[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?id=313606 Microscilla marina]'' ATCC 23134; '''VB''', ''[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Taxonomy/Browser/wwwtax.cgi?mode=Info&id=553239 Vibrio breoganii]''; '''BC''', ''[[wikipedia:Bacteroides|Bacteroides coprophilus]]''; '''MM''', ''[[wikipedia:Methanosarcina|Methanosarcina mazei]]''; '''MZ''', ''[[wikipedia:Methanosalsum|Methanosalsum zhilinae]]''; '''EH''', ''[[wikipedia:Anaerobutyricum_hallii|Eubacterium hallii]]'' DSM 3353; '''BSp''', ''[[wikipedia:Butyrivibrio|Butyrivibrio]]'' sp MB2005; '''BMT2''', ''[[wikipedia:Bacillus|Bacillus]]'' sp. MT2; '''FP''', ''Francisella philomiragia''; '''HP''', ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|Helicobacter pylori]]'' Hp H-16; '''RI''', ''[[wikipedia:Roseburia_inulinivorans|Roseburia inulinivorans]]''.]] | |||

ISC have very similar transposases to those of the IS''200''/IS''605'' family and are therefore part of the same super family. | |||

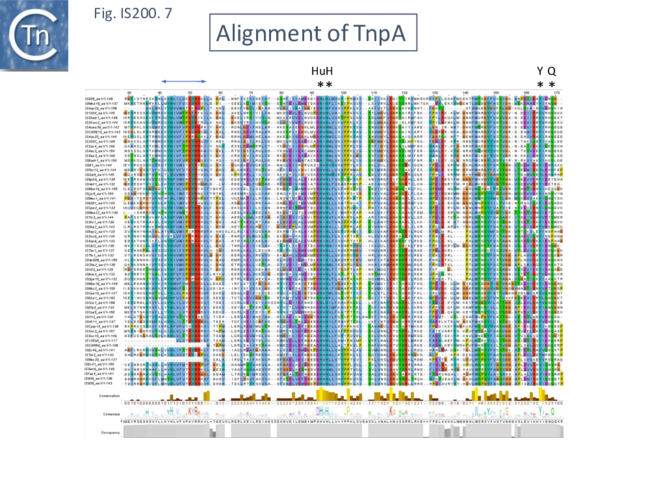

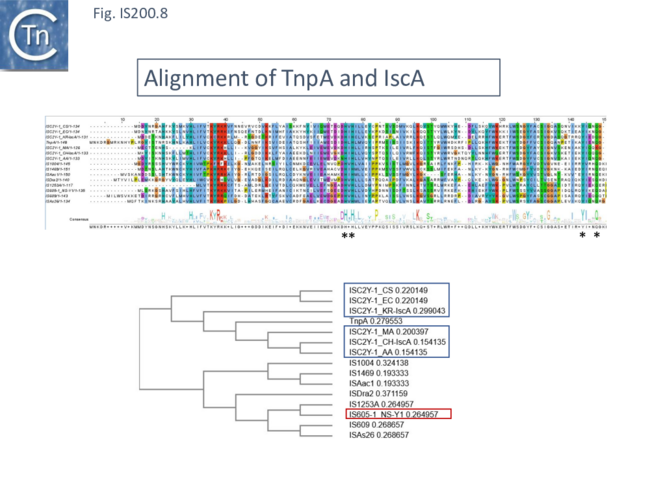

An alignment of full length TnpA from the IS''200''/IS''605'' group [[:File:FigIS200 605 7.png|(Fig. 200.7]]; [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/index.php ISfinder] November 2021) shows the highly conserved '''HuH''' triad, catalytic tyrosine ('''Y''') and important glutamine ('''Q''') residues all central to the transposition chemistry ([[:File:FigIS200 605 7.png|Fig. IS200.7]], [[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] and [[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]]) together with a number of other highly conserved amino acid positions. An alignment with the available IscA from the ISC group ([[:File:FigIS200 605 8.png|Fig. 200.8]] '''Top''') shows that these also include all the highly conserved TnpA amino acid positions and are therefore very closely related to TnpA. However, the IscA and TnpA proteins appear to fall into separate clades ([[:File:FigIS200 605 8.png|Fig. 200.8]] '''bottom''') with some overlap. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 7.png|center|thumb|650x650px|'''Fig. IS200.7.''' Alignment of TnpA proteins from the IS''200''/IS''605'' family. The data is drawn from ISfinder (November 2021). The alignment was performed with Clustal omega2 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalw2/) and drawn using Jalview Version 2. The '''HuH''', '''Y''' and '''Q''' residues are indicated. A consensus sequence is included beneath.]] | |||

Since IS families are defined by their transposases rather than their accessory genes, and those of ISC and the IS''200''/IS''605'' family are so similar, it seems reasonable to include the ISC group as a subgroup of the IS''200''/IS''605'' family (or [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] super family;<ref name=":29" /> ). For many of the archaeal elements, there is a small, potential 40-45 amino acid, peptide located upstream of the TnpB analogue. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 8.png|center|thumb|650x650px|'''Fig. IS200.8.''' Alignment of TnpA proteins from the IS''200''/IS''605'' family with IscA. The sequences for IS''200''/IS''605'' family members are from [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/index.php ISfinder] (November 2021) and the IscA proteins from Kapitonov et al.<ref name=":29" /> kindly supplied by [[wikipedia:Kira_Makarova|Kira Makarova]]. '''Top.''' The alignment was performed with Clustal omega2 and drawn using Jalview Version 2. The '''HuH''', '''Y''' and '''Q''' residues are indicated. A consensus sequence is included beneath. The IscA proteins from Kapitonov et al. are included. '''Bottom.''' Phylogenetic tree from the same alignment. The Sequences from Kapitonov et al. <ref name=":29" />are boxed.]] | |||

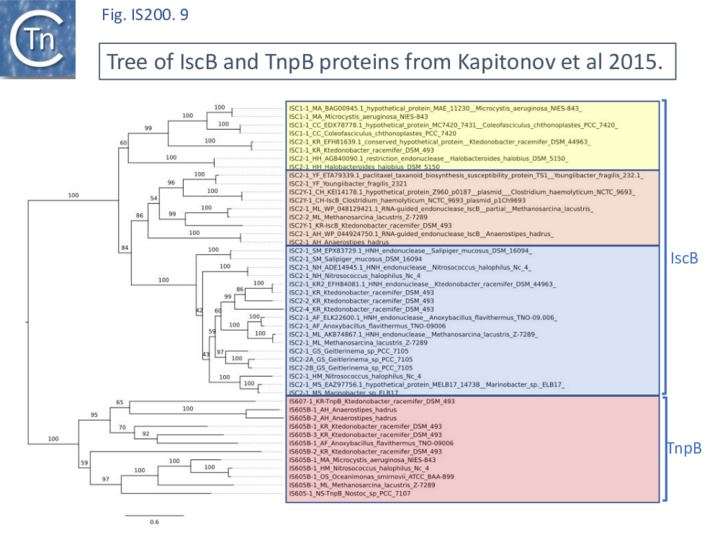

A tree based on the TnpB/IscB ([[:File:FigIS200 605 9.png|Fig. IS200.9]]) examples presented by Kapitonov, et al.,<ref name=":29" /> shows that the TnpB homologues form a clade separate from IscB and that the latter can be divided into two clades, IscB1 and IscB2. | |||

These considerations therefore reinforce the idea that the IS''200''/IS''605'' family and ISC group might be considered as a superfamily which includes a number of related accessory genes (''tnpB'', ''iscB1'', ''iscB2'' etc), which carry flanking DNA sequences with secondary structure potential and in which a Y1 HuH transposase assures the chemistry of transposition. A similar conclusion was also reached by Altae-Tran et al.<ref name=":30" /> .However, this picture is complicated by the identification of another group of transposable elements, the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/TnPedia/index.php/IS_Families/IS607_family IS''607'' family] in which ''tnpB'' is associated with a different type of transposase, in this case a serine site-specific recombinase ([https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/TnPedia/index.php/IS_Families/IS607_family IS''607'' family]). | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 9.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.9.''' Alignment of TnpA proteins from the IS''200''/IS''605'' family with IscA. The sequences for IS''200''/IS''605'' family members are from [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/index.php ISfinder] (November 2021) and the IscA proteins from Kapitonov et al.<ref name=":29" /> kindly supplied by [[wikipedia:Kira_Makarova|Kira Makarova]]. '''Top.''' The alignment was performed with Clustal omega2 and drawn using Jalview Version 2. The '''HuH''', '''Y''' and '''Q''' residues are indicated. A consensus sequence is included beneath. The IscA proteins from Kapitonov et al. are included. '''Bottom.''' Phylogenetic tree from the same alignment. The Sequences from Kapitonov et al. <ref name=":29" /> are boxed.]] | |||

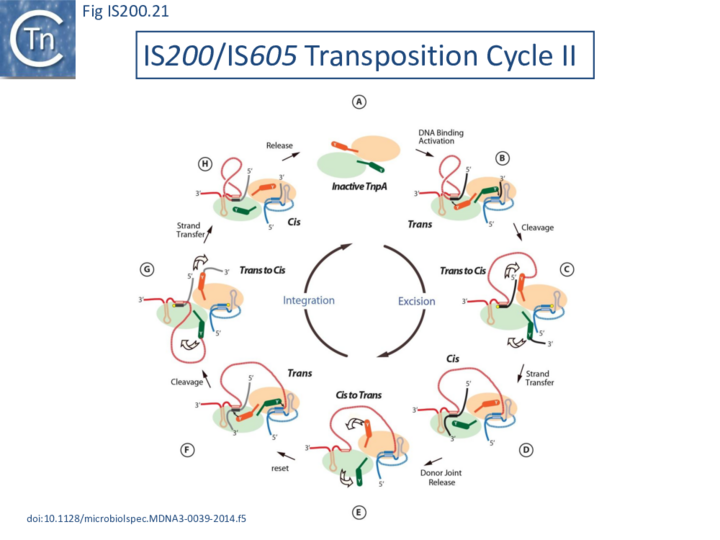

== Mechanism of IS''200''/IS''605'' single strand DNA transposition == | |||

=== | === Early models === | ||

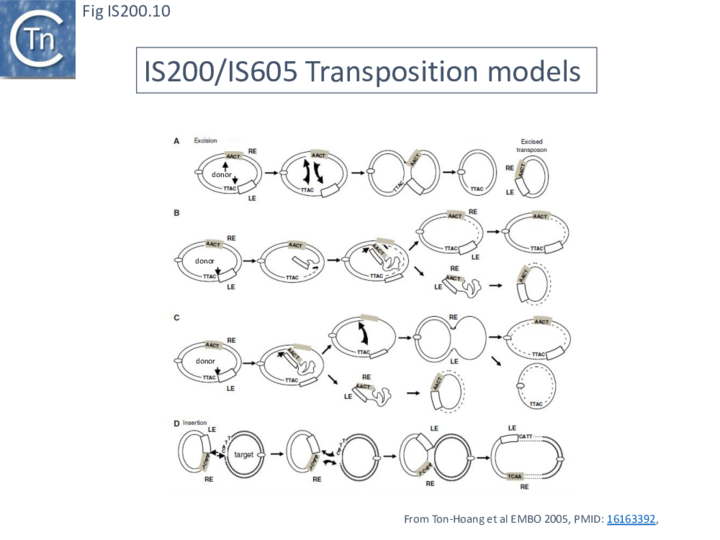

A number of alternative mechanisms were initially proposed to explain [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISHp608 IS''608''] transposition <ref name=":24" /> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 10.png|Fig. IS200.10]]). These all included the insertion of a double-strand circular transposon copy ([[:File:FigIS200 605 10.png|Fig. IS200.10]] '''D'''). One model ([[:File:FigIS200-4b.png|Fig. IS200.10]] '''A''') envisaged simultaneous or consecutive cleavage at '''LE''' and '''RE''' and reciprocal strand transfer would generate a [[wikipedia:Holliday_junction|'''H'''olliday '''j'''unction (HJ)]] which then could be resolved into double-strand circular copies of the transposon. The second ([[:File:FigIS200 605 10.png|Fig. IS200.10]] '''B''') cleavage at '''LE''' and replicative strand displacement using a 3’OH of the flanking donor DNA. This could assist formation of a single strand region accessible for cleavage of '''RE''' to generate a single-strand transposon circle which could be replicated into a double-strand copy. The third ([[:File:FigIS200 605 10.png|Fig. IS200.10]] '''C''') proposed cleavage at '''LE''' with displacement of the transposon strand to form a single strand loop. Subsequent ''in vitro'' and ''in vivo'' experiments (below) demonstrated that not only was [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISHp608 IS''608''] capable of excision as a single-strand DNA circle but that this could be inserted into a single strand target. | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 10.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.10.''' Proposed Models for [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] Transposition. Donor and target replicons are indicated (full and dotted lines, respectively). Dashed lines indicate newly replicated DNA. The conserved target sequence '''TTAC''' is also indicated. '''A)''' simultaneous or consecutive cleavage at '''LE''' and '''RE''' and reciprocal strand transfer would generate a [[wikipedia:Holliday_junction|'''H'''olliday '''j'''unction (HJ)]] which could be resolved into double-strand circular copies of the transposon; '''B)''' Cleavage at '''LE''' and replicated strand displacement using a 3’OH of the flanking donor DNA. This could assist the formation of a single strand circle region accessible for cleavage of '''RE''' to generate a single-strand transposon circle which could be replicated into a double-strand copy. '''C)''' Cleavage at '''LE''' with a displacement of the transposon strand to form a single strand loop. '''D)''' Integration. From Ton-Hoang et al.<ref name=":24" />.]] | |||

<br /> | |||

=== General transposition pathway === | |||

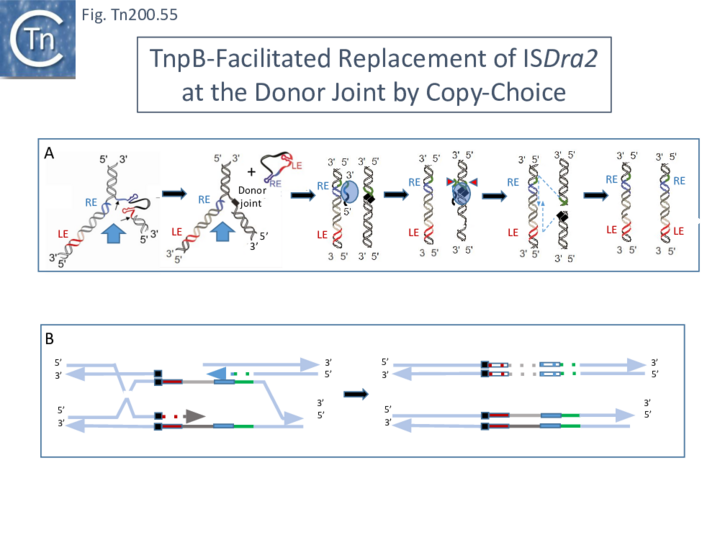

The transposition pathway of IS''200''/IS''605'' family members is shown in [[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]]. Much of the biochemistry was elucidated using an [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] cell-free ''in vitro'' system which recapitulates each step of the reaction. This requires purified TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> protein, single strand [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] DNA substrates and divalent metal ions such as Mg2+ or Mn2+ <ref name=":24" /><ref name=":7" /><ref name=":0" />. Similar and complementary results were also obtained with [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2'']''<ref name=":32" /><ref name=":25" /><ref name=":9" />''. The reactions are not only strictly dependent on single strand (ss) DNA substrates but are also strand-specific: only the “top” strand (defined as the strand carrying target sequence, TS, 5’ to the IS; [[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''top''') is recognized and processed whereas the “bottom” strand is refractory<ref name=":24" /> <ref name=":7" />. Cleavage of the top strand at the left and right cleavage sites (TS/CL and CR, note that TS is also the left cleavage site CL) ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''B''') leads to excision as a circular ssDNA intermediate with abutted left and right ends (transposon joint) ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''C''' bottom left). This is accompanied by rejoining of the DNA originally flanking the excised strand (donor joint). | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 11.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.11.''' '''Top''': [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] organization. The left (LE) and right (RE) ends with a subterminal hairpin (HP) are in red and blue, left and right cleavage sites (CL/TS and CR) are represented by black and blue boxes, respectively. Bottom left: Excision. '''(A)''' TnpA activity: top strand (active strand) structures are recognized and cleaved by TnpA (vertical arrows). '''(B)''' Upon cleavage, a 5′ phosphotyrosine bond (green cylinder) is formed with LE, and with the RE 3′ flank and 3′-OH (yellow circle) is formed at the left flank and RE. '''(C)''' Excision of the IS''608'' single-strand circle intermediate with abutted LE and RE (RE–LE junction or transposon joint) accompanied by the formation of donor joint retaining the target sequence. '''Bottom right''': Integration. '''(D)''' Transposon circle with the transposon joint and target DNA (black) with the target site. '''(E)''' TnpA catalyzes the cleavage of transposon joint and single-strand target. '''(F)''' Integration.]] | |||

The transposon joint is then cleaved ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.5]] '''E''' bottom right) and integrated into a single strand conserved element-specific target sequence (TS) where the left end invariably inserts 3’ to TS ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.5]] '''F'''). This target specificity is another unusual feature of IS''200''/IS''605'' transposition. The target sequence is characteristic of the particular family member and, although it is not part of the IS, it is essential for further transposition because it is also the left end cleavage site CL of the inserted IS <ref name=":24" /> (''The Single strand Transpososome and Cleavage site recognition'') and is therefore intimately involved in the transposition mechanism. | |||

=== | === TnpA, Y1 transposases and transposition chemistry === | ||

IS''200''/IS''605'' family transposases belong to the '''HUH enzyme superfamily.''' All contain a conserved amino-acid triad composed of Histidine (H)-bulky hydrophobic residue (U)-Histidine (H)<ref>{{#pmid:8374079}}</ref> providing two of three ligands required for coordination of a divalent metal ion that localizes and prepares the scissile phosphate for nucleophilic attack. HUH proteins catalyze ssDNA breakage and joining with a unique mechanism. They all catalyse DNA strand cleavage using a transitory covalent 5' phosphotyrosine enzyme-substrate intermediate and release a 3' OH group <ref name=":1" /> ([[General Information/Major Groups are Defined by the Type of Transposase They Use#Groups%20with%20HUH%20Enzymes|Groups with HUH Enzymes]]; [[:File:1.10.1.png|Fig.7.5]]). | |||

The | The HUH enzyme family also includes other transposases of the [[IS Families/IS91-ISCR families|IS''91''/IS''CR'' and Helitron families]] as well as proteins involved in DNA transactions essential for plasmid/virus rolling circle replication (Rep; not to be confused with the TnpA<sub>REP</sub>/REP system described in [[IS Families/IS200-IS605 family#Y1 transposase domestication|Domestication]]) and plasmid conjugation (Mob/relaxase) ([[General Information/Major Groups are Defined by the Type of Transposase They Use#Groups with HUH Enzymes|Groups with HUH Enzymes]]; [[:File:1.10.1.png|Fig.7.5]]). | ||

IS''200''/IS''605'' transposases are single-domain proteins containing a single catalytic tyrosine residue, called '''Y1 transposase'''. They use the tyrosine residue (Y127 for IS608) as a nucleophile to attack the phosphodiester link at the cleavage sites (vertical arrows in [[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''A''' and '''D'''). Since cleavages at both IS ends occur on the same strand, the polarity of the reaction implies that the enzyme forms a covalent 5’-phosphotyrosine bond with the IS at LE producing a 3’-OH on the DNA flank and a 5’-phosphotyrosine bond at the RE flank producing a 3’-OH on RE itself ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''B'''). The released 3′-OH groups then act as nucleophiles to attack the appropriate phospho-tyrosine bond resealing the DNA backbone in one case and generating a single-strand DNA transposon circle in the other ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''C'''). The same polarity is applied to the integration step ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]] '''D''', '''E''' and '''F'''). As an important mechanistic consequence of this chemistry, IS''200''/IS''605'' transposition occurs without loss or gain of nucleotides. ''In vitro'', the reaction requires only TnpA and does not require host cell factors. | |||

IS''200''/IS''605'' | |||

=== TnpA overall structure === | |||

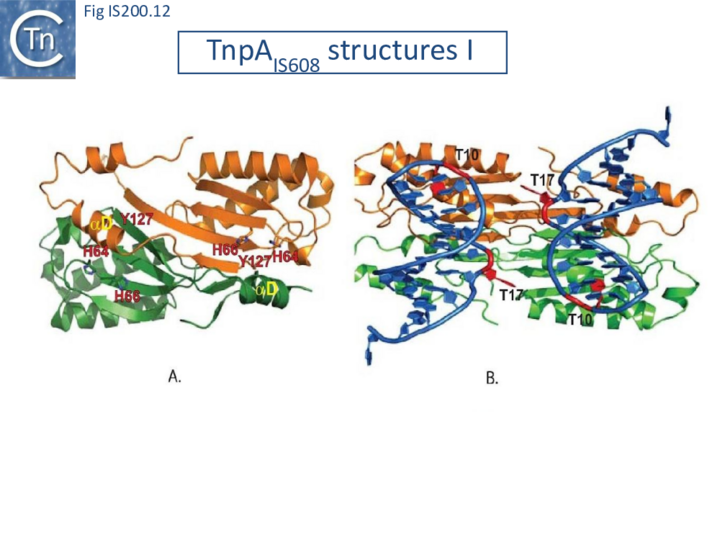

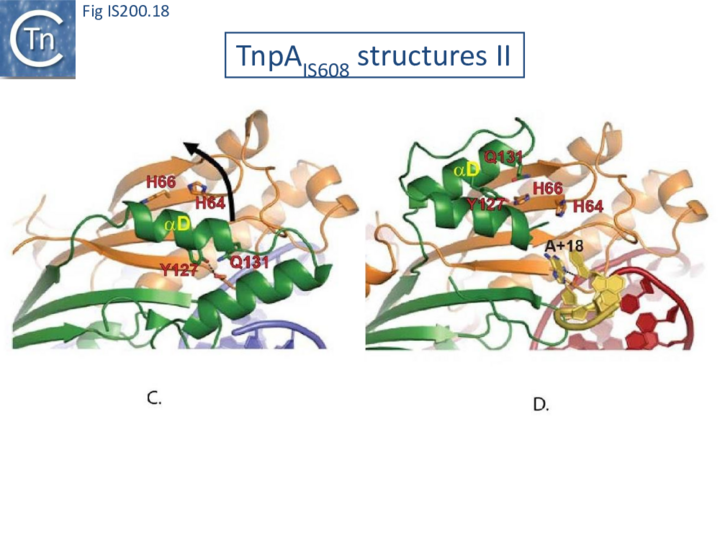

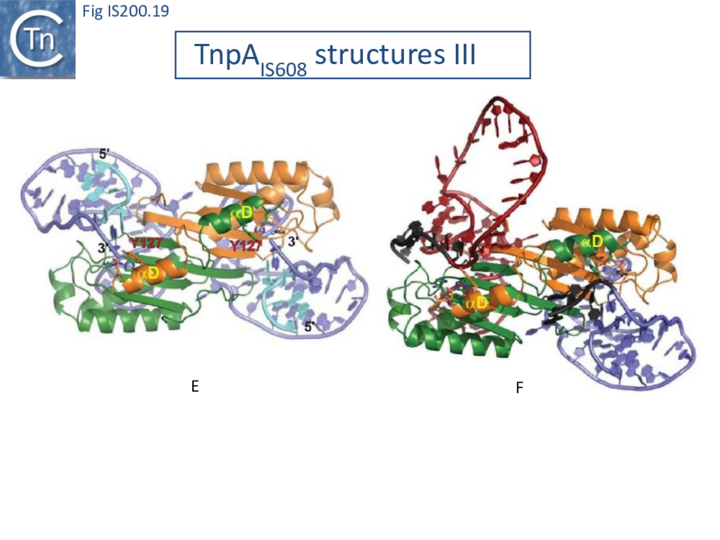

Crystal structures of Y1 transposases have been determined for three family members: [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] (TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub>) from ''[[wikipedia:Helicobacter_pylori|Helicobacter pylori]]'' <ref name=":23" /><ref name=":0" /> [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] (TnpA<sub>IS''Dra2''</sub>) from ''[[wikipedia:Deinococcus_radiodurans|Deinococcus radiodurans]] <ref name=":9" />'' and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISC1474 IS''C1474''] from ''[[wikipedia:Sulfolobus_solfataricus|Sulfolobus solfataricus]]''<ref name=":162">{{#pmid:16340015}}</ref>. In contrast to most characterised '''HUH enzymes''', which are usually monomeric and have two catalytic tyrosines, '''Y1 transposases''' form obligatory dimers with two active sites ([[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]] '''A'''). The two monomers dimerize by merging their β-sheets into one large central β-sheet sandwiched between α-helices. Each catalytic site is constituted by the '''HUH motif''' from one TnpA monomer (H64 and H66 in the case of TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub>) and a catalytic tyrosine residue (Y127) located in the C-terminal αD helix tail of the other monomer ([[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]] '''A'''). This is joined to the body of the protein by a flexible loop (trans configuration, Active site assembly and Catalytic activation and [[IS Families/IS200 IS605 family#Transposition cycle: the trans.2Fcis rotational model|Transposition cycle: the trans/cis rotational model]]). | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 12.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.12.''' '''(A)''' Crystallographic structure of TnpA alone. The two monomers of the TnpA dimer are colored green and orange, respectively. Positions of helix αD and catalytic residues are shown. '''(B)''' Co structure TnpA–RE HP22. HP22 is shown in blue. The extrahelical T17 and the T located in the hairpin loop are indicated in red (6). Note that in the TnpA–HP22 co-structure, binding sites for the hairpins are located on the same face of the TnpA dimer whereas the two catalytic sites are formed on the opposite surface (A, C–F).]] | |||

The TnpA enzyme active sites are believed to adopt two functionally important conformations: the trans configuration described above ([[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]] '''A'''), in which each active site is composed of the '''HUH motif''' supplied by one monomer with the tyrosine residue supplied by the other, and the cis configuration, in which both motifs are contributed by the same monomer (IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 1''' '''below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O. Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). | |||

The trans conformation is active during cleavage where Tyrosine acts as nucleophile whereas the cis conformation is thought to function during strand transfer where the 3’OH is the attacking nucleophile ([[IS Families/IS200 IS605 family#Transposition cycle: the trans.2Fcis rotational model|Transposition cycle: the trans/cis rotational model]]). Only the trans configuration of TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> and TnpA<sub>IS''Dra2''</sub> has yet been observed crystallographically <ref name=":23" /><ref name=":9" /> but the existence of the cis configuration is supported by biochemical data <ref name=":82">{{#pmid:23345619}}</ref>.<br /><center> | |||

<center> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

![[File:IS200 S605-video-1.mp4|center|380x380px]]'''<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' video 1</small>''' | ![[File:IS200 S605-video-1.mp4|center|380x380px]]'''<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' video 1</small>''' | ||

| Line 103: | Line 146: | ||

</center> | </center> | ||

=== The Single strand Transpososome === | |||

The key machinery for transposition is the higher-order protein-DNA complex, the transpososome (or synaptic complex) which contains both transposase and two IS DNA ends with or without target DNA. Transpososome formation, stability, and the temporal changes in a configuration which occur during the transposition cycle have been characterized for | The key machinery for transposition is the higher-order protein-DNA complex, the transpososome (or synaptic complex) which contains both transposase and two IS DNA ends with or without target DNA. Transpososome formation, stability, and the temporal changes in a configuration which occur during the transposition cycle have been characterized for TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> by crystallographic and biochemical approaches. | ||

Although for technical reasons it was not possible to obtain structures with both LE and RE hairpins together, co-crystal structures with either LE or RE showed that a TnpA dimer binds two subterminal DNA hairpins suggesting that it could bind both '''LE''' and '''RE''' ends simultaneously. Binding sites for the hairpins are located on the same face of the TnpA dimer while the two catalytic sites are formed on the opposite surface ([[:File:Fig. IS200.6.png|Fig. IS200.6]] '''A''' and '''B)''' (IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 2 below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O. Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). The hairpin forms a distorted helix anchored by base interactions at the foot (IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 2 below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O. Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). | |||

<center> | <center> | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

![[File:IS200 S605-video-2 1.mp4|center|380x380px]]'''<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' video 2</small>''' | ![[File:IS200 S605-video-2 1.mp4|center|380x380px]]'''<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' video 2</small>''' | ||

|}</center><br /> | |}</center> | ||

<br /> | |||

==== Substrate recognition ==== | |||

A key feature of TnpA is that it is only active on one strand, the “top” strand. The [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] ends carry subterminal imperfect hairpins. In addition to specific sequences on the loops, the irregularities on the hairpins help the enzyme to distinguish between “top” and “bottom” strands <ref name=":23" /> <ref name=":9" />. The initial co-crystal structure was obtained with | A key feature of TnpA is that it is only active on one strand, the “top” strand. The [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] ends carry subterminal imperfect hairpins. In addition to specific sequences on the loops, the irregularities on the hairpins help the enzyme to distinguish between “top” and “bottom” strands <ref name=":23" /><ref name=":9" />. The initial co-crystal structure was obtained with TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> and a 22nt imperfect RE hairpin (HP22) including its characteristic extrahelical T17 located mid-way along the DNA stem ([[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]] and [[:File:FigIS200 605 13.png|Fig. IS200.13]]). In addition to a number of backbone contacts with HP22, TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> also shows several base-specific contacts, in particular with T10 in the loop and the extrahelical T17<ref name=":23" /> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 12.png|Fig. IS200.12]] '''B'''). | ||

Although most members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group, which includes [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''], have imperfect palindromes with extrahelical bases or bulges, some members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group (e.g [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1541 IS''1541'']) include perfect hairpins. Whether base-specific interactions with the loop sequence is exclusively responsible for strand-specific activity of the corresponding transposase remains to be clarified.<center> | Exchange of T10 and neighboring T nucleotides in the loop abolished binding whereas the exchange of T17 for an A significantly reduced but did not eliminate binding <ref name=":102">{{#pmid:21745812}}</ref>. Similar studies with TnpA<sub>IS''Dra2''</sub> showed that it also recognises a similarly located T in the hairpin loop of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] and that this is essential for binding <ref name=":9" /> . Instead of an extrahelical T, [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] '''LE''' and '''RE''' include a bulge caused by two mismatched nucleotides (G and T) in the hairpin stem. These unpaired nucleotides are specifically recognized and stabilized by the protein. Again, mutation of the T (to C which, in this case, eliminates the bulge to generate a GC base pair in the stem) greatly reduces binding (IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3A below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O.Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). | ||

Although most members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS605 IS''605''] group, which includes [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''], have imperfect palindromes with extrahelical bases or bulges, some members of the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''] group (e.g [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS200 IS''200''], [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1541 IS''1541'']) include perfect hairpins. Whether base-specific interactions with the loop sequence is exclusively responsible for strand-specific activity of the corresponding transposase remains to be clarified. | |||

<center> | |||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

![[File:IS200 S605-video-3A.mp4|center|380x380px]]<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3A'''</small> | ![[File:IS200 S605-video-3A.mp4|center|380x380px]]<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3A'''</small> | ||

|}</center> | |}</center> | ||

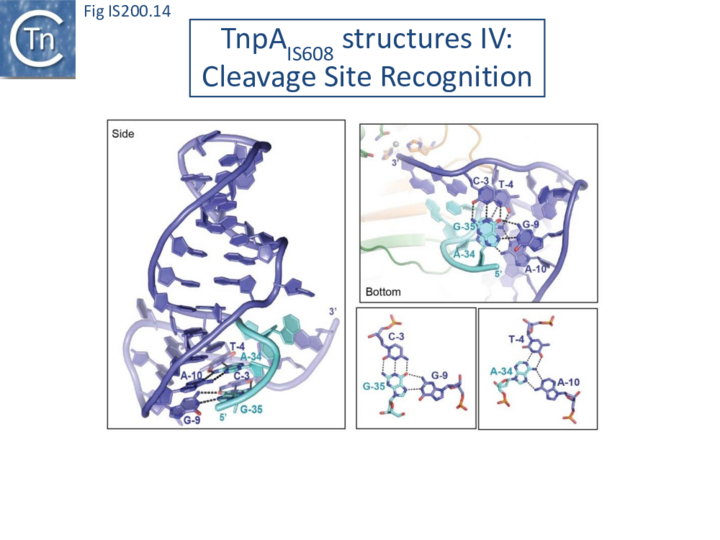

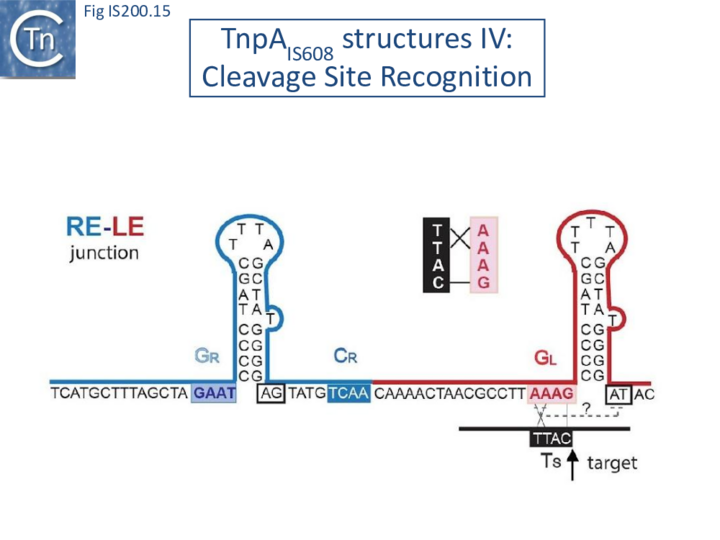

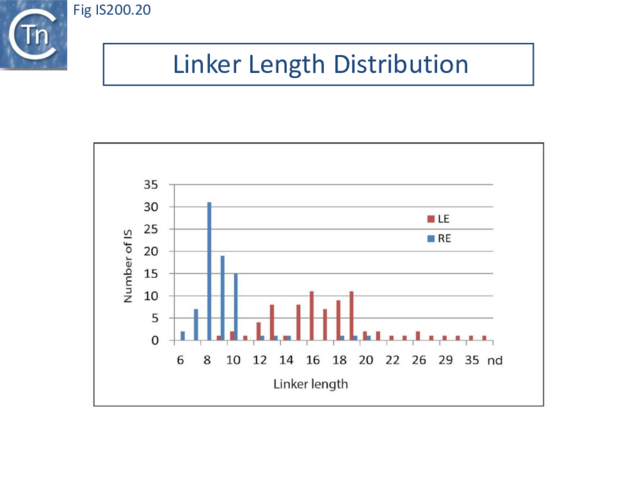

The left (CL/TS) and right (CR) [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] cleavage sites (TTACl and TCAAl respectively, where l represents the point of cleavage) are located some distance from the subterminal recognition hairpins (19 nt at LE and 10 nt at RE) ([[:File: | ==== Cleavage site recognition ==== | ||

[[ | The left (CL/TS) and right (CR) [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] cleavage sites (TTACl and TCAAl respectively, where l represents the point of cleavage) are located some distance from the subterminal recognition hairpins (19 nt at '''LE''' and 10 nt at '''RE''') ([[:File:FigIS200 605 13.png|Fig. IS200.13]]). The system is asymmetric because the two distinct cleavage sites are separated from the hairpins by linkers of different lengths and the CL/TS sequence does not form part of IS while CR does. | ||

[[File:FigIS200 605 13.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.13.''' Canonical and noncanonical base interactions in '''(A)''' '''left end''' (LE) and '''(B)''' '''right end''' (RE). LE and RE (red and blue). Cleavage sequences CL or CR (black or dark blue boxes); guide sequences GL and GR pink or light blue, respectively. Two nucleotides at the 3′ foot of HPL, R involved in triplet formation are highlighted by bold and in a black frame. LE and RE and the base paring within HPL and HPR are shown. Insets show interactions between cleavage and guide sequences. Filled lines: canonical base interactions, dotted lines: additional noncanonical base interactions.]] | |||

Structural studies revealed that the cleavage sites are recognized in a unique way that does not involve direct sequence recognition by TnpA. Instead, an internal part of the IS sequence is co-opted to recognize different cleavage sites allowing TnpA to catalyze both excision and integration of the element with a single DNA binding domain. | Structural studies revealed that the cleavage sites are recognized in a unique way that does not involve direct sequence recognition by TnpA. Instead, an internal part of the IS sequence is co-opted to recognize different cleavage sites allowing TnpA to catalyze both excision and integration of the element with a single DNA binding domain. | ||

Internal transposon sequences, the left (GL) and right (GR) tetranucleotide guide sequences, AAAG and GAAT, located 5’ to the foot of the hairpins ([[:File:Fig. IS200.7.png|Fig. IS200.7]]), recognize their respective cleavage sites by direct base interactions. These GL/CL and GR/CR interactions involve 3 of the 4 nt of GL and GR. They include both [[wikipedia:Base_pair|canonical Watson-Crick interactions]] and in the case of RE, non-canonical interactions resulting in base triplets ([[:File: | Internal transposon sequences, the left ('''GL''') and right ('''GR''') tetranucleotide guide sequences, AAAG and GAAT, located 5’ to the foot of the hairpins ([[:File:Fig. IS200.7.png|Fig. IS200.7]]), recognize their respective cleavage sites by direct base interactions. These GL/CL and GR/CR interactions involve 3 of the 4 nt of GL and GR. They include both [[wikipedia:Base_pair|canonical Watson-Crick interactions]] and in the case of '''RE''', non-canonical interactions resulting in base triplets ([[:File:FigIS200 605 13.png|Fig. IS200.13]] and [[:File:FigIS200 605 14.png|Fig. IS200.14]], bases joined by both regular and dotted lines respectively). In the case of '''LE''' and the transposon joint, base triples (dotted lines) are suggested from biochemical data <ref name=":102" /> (IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3B below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O. Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). | ||

[[ | [[File:FigIS200 605 14.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.14.''' Structure of the co-complex TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub>–RE35 adapted from reference 8 showing the active site and the base pairs between '''CR''' ('''TCAA''', dark blue) and '''GR''' ('''GAAT''', light blue). The gray sphere is bound Mn2+. '''Right''': Two base triplets observed in the TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub>–RE35 complex.]] | ||

<center> | <center> | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

![[File:IS200 S605-video-3B.mp4|center|381x381px]]<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3B'''</small> | ![[File:IS200 S605-video-3B.mp4|center|381x381px]]<small>IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 3B'''</small> | ||

|} | |} | ||

</center>These interactions place the scissile phosphate precisely into the two active sites of | </center> | ||

[[ | These interactions place the scissile phosphate precisely into the two active sites of TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> for nucleophilic attack by the catalytic Y127. Interestingly, the base-pairing patterns responsible for cleavage site recognition are similar at '''LE''', '''RE''' and the target site in spite of sequence differences ([[:File:FigIS200 605 13.png|Fig. IS200.13]], [[:File:FigIS200 605 14.png|Fig. IS200.14]], [[:File:FigIS200 605 15.png|Fig. IS200.15]]). Since TS is also CL, this type of recognition not only explains the requirement for the TS located at the left end of the inserted IS ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]], [[:File:FigIS200 605 15.png|Fig. IS200.15]]) for further transposition, but also the target specificity. Upon integration, TS is presumably recognized by the GL present on the excised transposon joint. Note that the transposon joint contains only the '''LE''' guide sequence GL but not the '''LE''' cleavage site CL ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]], [[:File:FigIS200 605 15.png|Fig. IS200.15]]). | ||

[[File:FigIS200 605 15.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.15.''' Target recognition: single-strand transposon joint ('''RE'''–'''LE''' junction) and target Ts are presented. For simplicity, only the recognition of the target cleavage site is indicated. '''LE''' and '''RE''' are shown in red and blue. Cleavage sequences '''C<sub>L</sub>''' or '''C<sub>R</sub>''' are placed in black or dark blue boxes; guide sequences '''G<sub>L</sub>''' and '''G<sub>R</sub>''' are framed in pink and light blue, respectively. Two nucleotides at the 3′ foot of the left and right hairpin structures '''HP<sub>L</sub>''' and '''HP<sub>R</sub>''' involved in triplet formation are highlighted by bold and are in a black frame. Nucleotide sequences of '''LE''' and '''RE''' and the base paring within '''HP<sub>L</sub>''' and '''HP<sub>R</sub>''' are shown. The inset figures describe the interactions between the cleavage sequences and guide sequences. The filled lines indicate canonical base interactions and the dotted lines indicate additional noncanonical base interactions.]] | |||

Similar crystal structures were obtained with TnpA<sub>IS''Dra2''</sub> (see also Single strand DNA ''in vivo'') with a similar interaction network between the guide sequences and cleavage sites. | |||

The [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] transpososome is structurally very similar to those of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] despite only 34% sequence identity of the transposases. It is important to note that the target sequence in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] is a pentanucleotide instead of a tetranucleotide as in [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608'']. The fifth nucleotide in the [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=ISDra2 IS''Dra2''] sequence is however not involved in DNA-DNA interactions but in DNA-protein interaction<ref name=":9" />. | |||

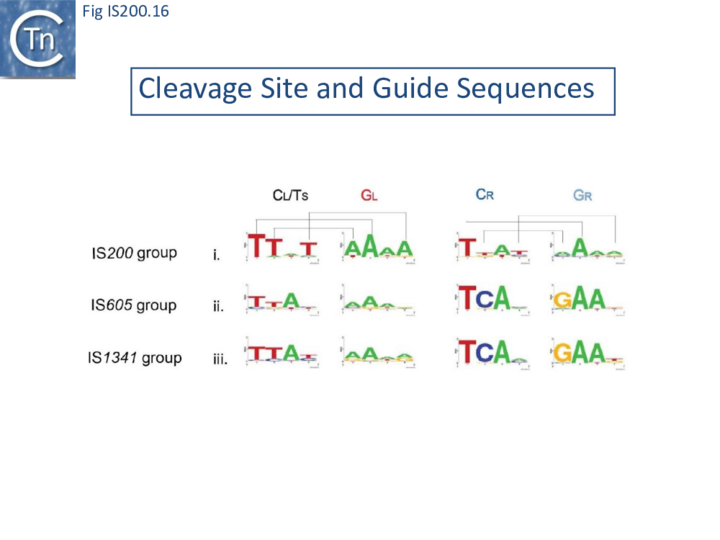

The potential cleavage site recognition mode (i.e. the canonical interaction network between CL,R and GL,R) is indeed well conserved throughout the family ([[:File:FigIS200 605 16.png|Fig. IS200.16]]). | |||

[[File:FigIS200 605 16.png|center|thumb|720x720px|'''Fig. IS200.16.''' Multiple sequence alignment of the cleavage sites and guide sequences using [http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/ Weblogo] was carried out on 38, 43 and 23 members of the IS''200'' '''(i)''', the IS''605'' '''(ii)''', and [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS1341 IS''1341''] '''(iii)''' groups, respectively.]] | |||

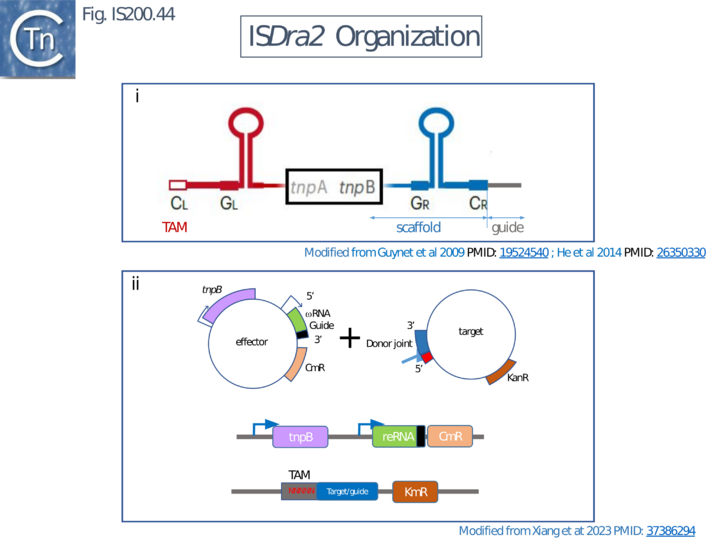

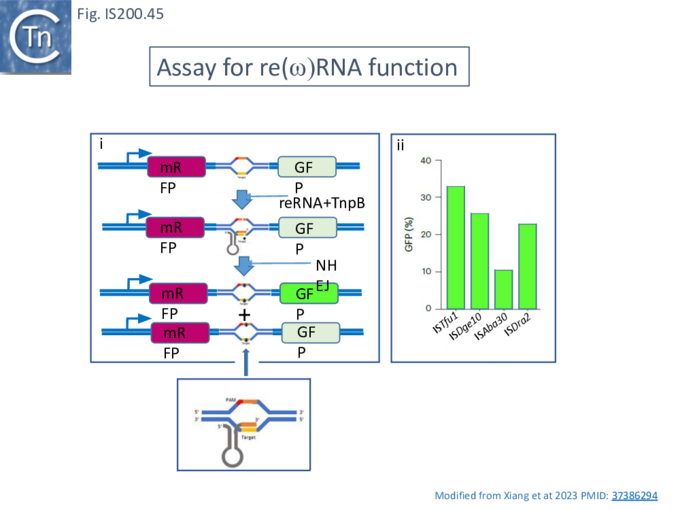

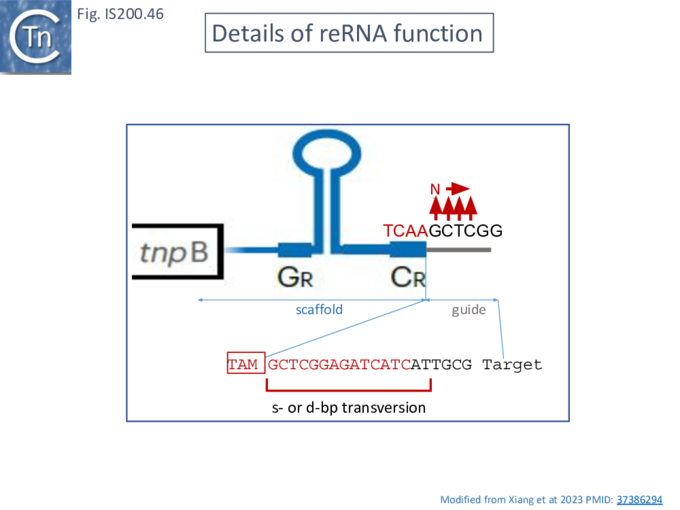

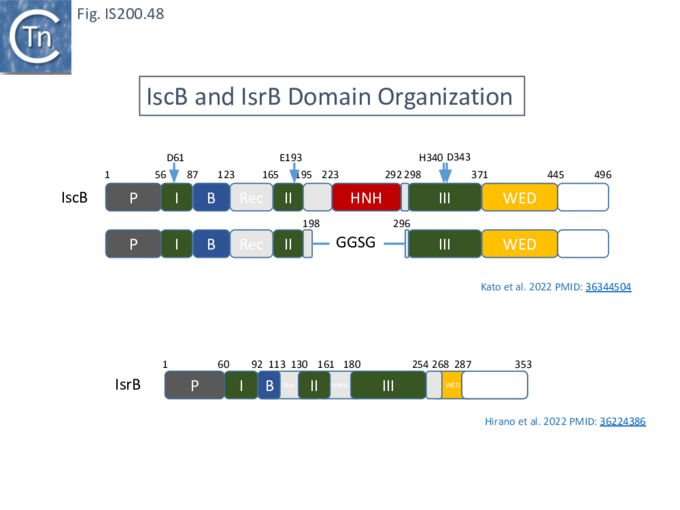

This model has been validated ''in vitro'' and ''in vivo'' by showing that it is possible to modify cleavage sites by changing corresponding guide sequences. Moreover, in the case of [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''], modifications of GL in the transposon joint generate predictable changes in insertion site-specificity of the element <ref name=":52">{{#pmid:19524540}}</ref>. The [https://tncentral.ncc.unesp.br/ISfinder/scripts/ficheIS.php?name=IS608 IS''608''] recognition system has also been modified to include additional sequences which assist more specific targeting of insertions<ref>{{#pmid:29635476}}</ref>. | |||

==== Active site assembly and Catalytic activation ==== | |||

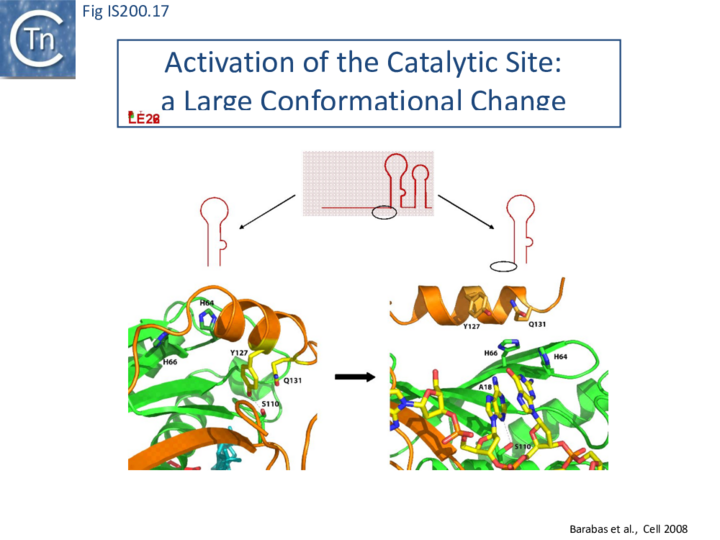

Comparison of crystal structures of different TnpA protein-DNA complexes <ref name=":23" /><ref name=":0" /> <ref name=":162" /> revealed TnpA in both active and inactive configurations. In both the free TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub> dimer and TnpA<sub>IS''608''</sub>-DNA complexes bound to a “minimal” HP22 hairpin (which does not include the guide sequence), the catalytic tyrosine residue (Y127) points away from the HUH motif (H64 and H66) and therefore cannot act as a nucleophile <ref name=":23" /> ([[:File:FigIS200 605 11.png|Fig. IS200.11]]). | |||

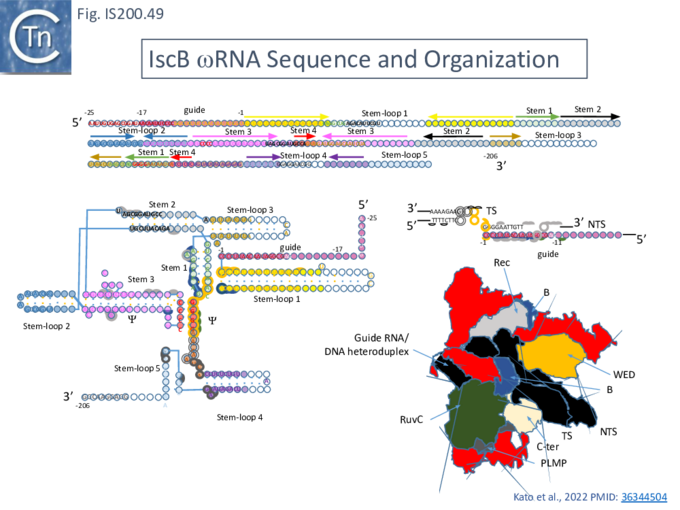

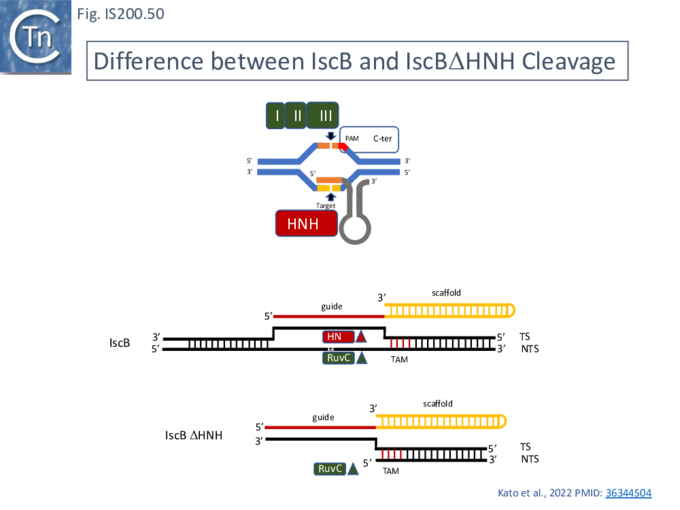

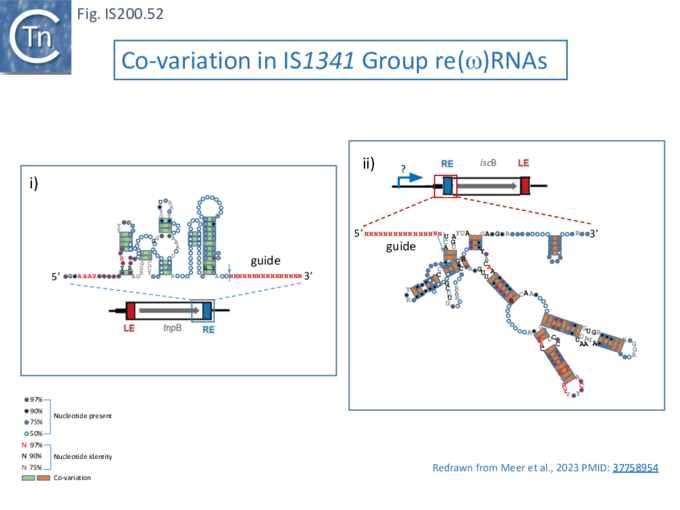

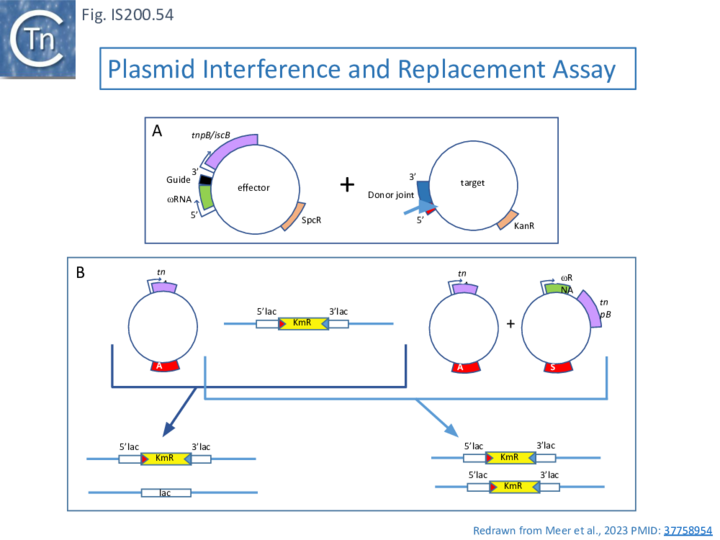

The enzyme is therefore in an inactive conformation. Binding to the appropriate substrate containing the 4 nucleotide guide sequence 5’ to the hairpin foot (compare [[:File:FigIS200 605 17.png|Fig. IS200.17]] '''left''' and '''right''') triggers a change in TnpA configuration that permits assembly of functional active sites. A single A (A+18, [[:File:FigIS200 605 13.png|Fig. IS200.13]] and [[:File:FigIS200 605 14.png|Fig. IS200.13]]) in the guide sequence present in both GL and GR does not participate in base interactions with the cleavage site. On formation of the CL(R)/GL(R) base interaction network, this single base penetrates the structure and forces the C-terminal αD helix carrying Y127 closer to the '''HuH motif''' placing it in the correct position poised for catalysis <ref name=":0" /> (compare [[:File:FigIS200 605 17.png|Fig. IS200.17]] '''left''' and '''right'''; [[:File:FigIS200 605 18.png|Fig. IS200.18]])(IS''200''/IS''605'' '''video 4 below'''; kindly supplied by [https://www.embl.de/research/units/scb/barabas/ O. Barabas] and [https://www-mslmb.niddk.nih.gov/dyda/dydalab.html Fred Dyda]). | |||