IS Families/IS200 IS605 family

Historical

One of the founding members of this group, IS200, was identified in Salmonella typhimurium [1] as a mutation in hisD (hisD984) which mapped as a point mutation but which did not revert and was polar on the downstream hisC gene (see [2]). S. typhimurium LT2 was found to contain six IS200 copies and the IS was unique to Salmonella [3]. Further studies [4] showed that the IS did not carry repeated sequences, either direct or inverted, at its ends, and that removal of 50 bp at the transposase proximal end (which includes a structure resembling a transcription terminator) removed the strong transcriptional block. IS200 elements from S. typhimurium and S. abortusovis revealed a highly conserved structure of 707–708 bp with a single open-reading-frame potentially encoding a 151 aa peptide and a putative upstream ribosome-binding-site [5].

It has been suggested that a combination of inefficient transcription, protection from impinging transcription by a transcriptional terminator, and repression of translation by a stem-loop mRNA structure. All contribute to tight repression of transposase synthesis [6]. However, although IS200 seems to be relatively inactive in transposition [7], it is involved in chromosome arrangements in S. typhimurium by recombination between copies [8].

A second group of “founding” members of this family was, arguably, IS1341 from the thermophilic bacterium PS3 [9], IS891 from Anabaena sp. M-131 [10] and IS1136 from Saccharopolyspora erythraea [11]. The “transposases” of both elements were observed to be associated in a single IS, IS605, from the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori [12]. It was identified in many independent isolates of H. pylori and is now considered to be a central member which defines this large family. IS605 was shown to possess unique, not inverted repeat, ends; did not duplicate target sequences during transposition; and inserted with its left (IS200-homolog) end abutting 5'-TTTAA or 5'-TTTAAC target sequences [13]. Additionally, a second derivative, IS606, with only 25% amino acid identity in the two proteins (orfA and orfB) was also identified in many of the H. pylori isolates including some which were devoid of IS605. The Berg lab also identified another H. pylori IS, IS607 [14] which carried a similar IS1341-like orf (orfB) but with another upstream orf with similarities to that of the mycobacterial IS1535 [15] annotated as a resolvase due the presence of a site-specific serine recombinase motif. Another IS605 derivative, ISHp608, which appeared widely distributed in H. pylori was shown to transpose in E. coli, required only orfA to transpose and inserted downstream from a 5’-TTAC target sequence [16].

General

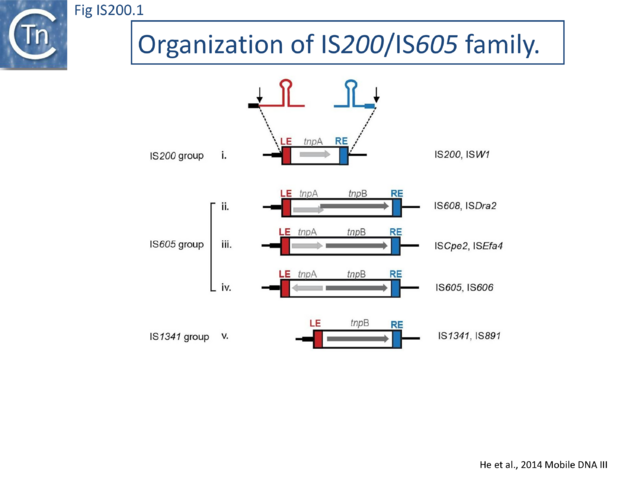

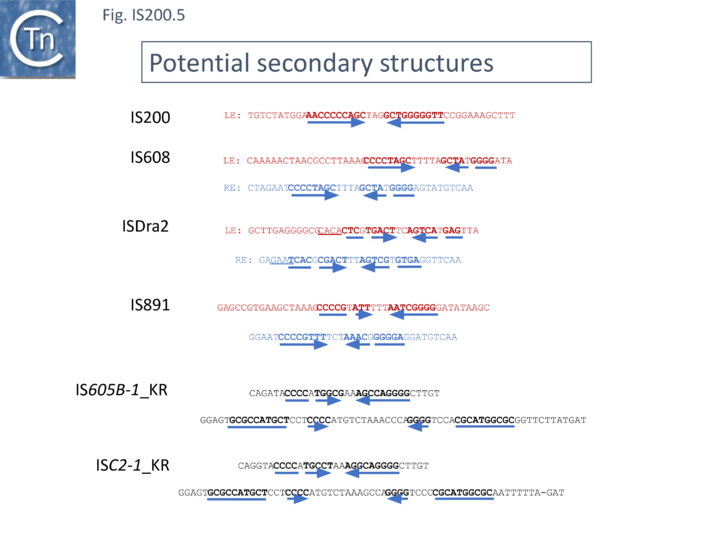

The IS200/IS605 family members transpose using obligatory single strand(ss) DNA intermediates[17] by a mechanism called “peel and paste”. They differ fundamentally in the organization from classical IS. They have sub-terminal palindromic structures rather than terminal IRs (Fig. IS200.1) and insert 3’ to specific AT-rich tetra- or penta-nucleotides without duplicating the target site.

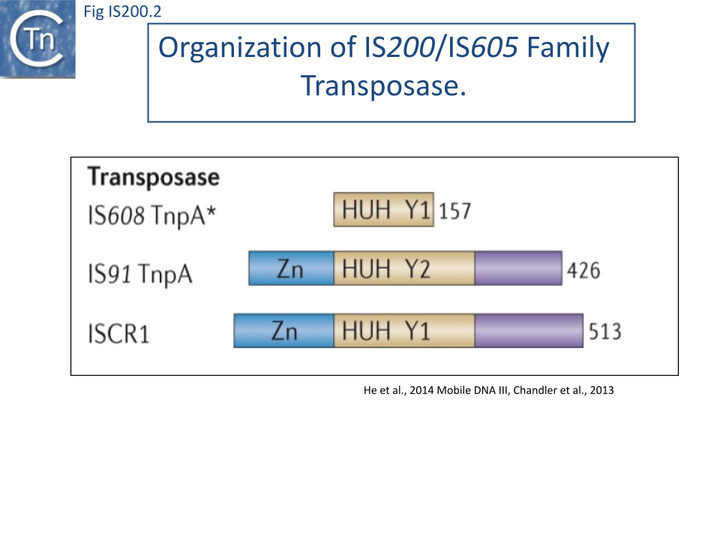

The transposase, TnpA, is a member of the HUH enzyme superfamily (Relaxases, Rep proteins of RCR plasmids/ss phages, bacterial and eukaryotic transposases of IS91/ISCR and Helitrons[18][19])(Fig. IS200.2) which all catalyze cleavage and rejoining of ssDNA substrates.

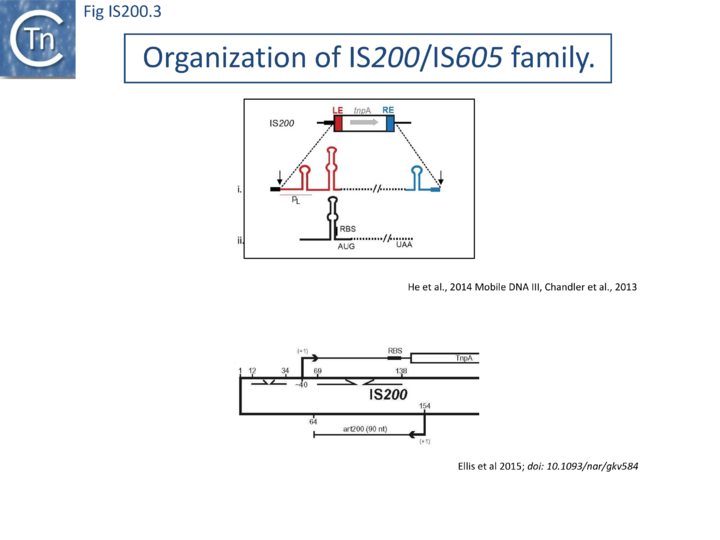

IS200, the founding member (Fig. IS200.3), was identified 30 years ago in Salmonella typhimurium[20] but there has been renewed interest for these elements since the identification of the IS605 group in Helicobacter pylori[21][22][23]. Studies of two elements of this group, IS608 from H. pylori and ISDra2 from the radiation resistant Deinococcus radiodurans, have provided a detailed picture of their mobility [24][25][26][27][28][29][30].

Distribution and Organization

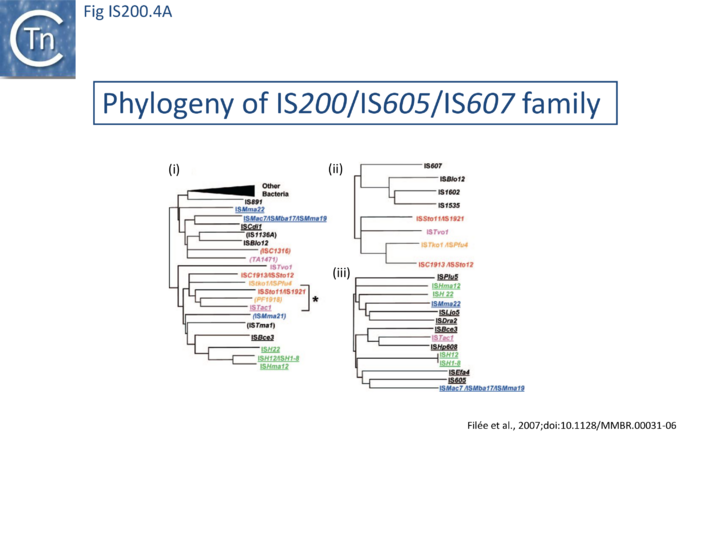

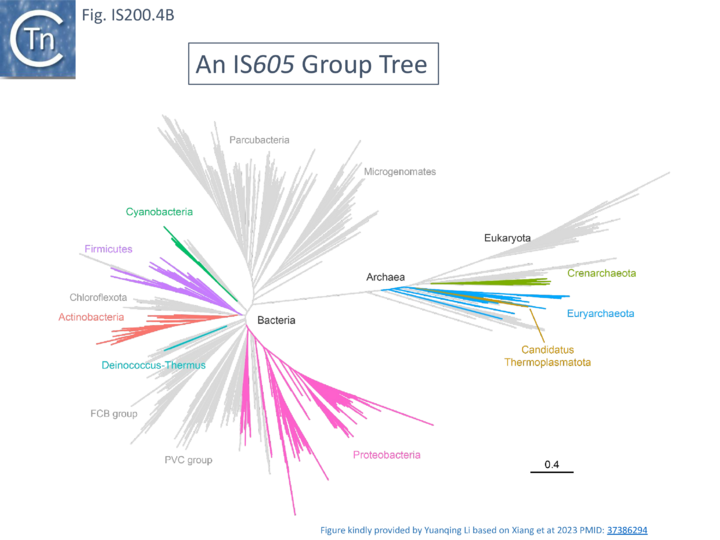

The family is widely distributed in prokaryotes with more than 153 distinct members (89 are distributed over 45 genera and 61 species of bacteria, and 64 are from archaea). It is divided into three major groups based on the presence or absence and on the configuration of two genes: the transposase tnpA (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/cog/COG1943/), sufficient to promote IS mobility in vivo and in vitro and tnpB (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/research/cog/cog/COG0675/) (Fig. IS200.1) initially of unknown function and not required for transposition activity but now known to de an RNA-guide endonuclease (see TnpB below) . These groups are: IS200, IS605 and IS1341. TnpB is also present in another IS family, IS607, which uses a serine-recombinase as a transposase. In the phylogeny of this group (Fig. IS200.4A) of IS, both tnpB and tnpA of bacterial or archaeal origin are intercalated, suggesting some degree of horizontal transfer between these two groups of organisms[31].

Isolated copies of IS200-like tnpA can be identified in both bacteria and archaea[32]. Full length copies of IS605-like elements are also found in bacteria and several archaea and all have corresponding MITEs (Miniature Inverted repeat Transposable Elements) derivatives in their host genomes.

The IS200 group

IS200 group members encode only tnpA, and are present in gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria and certain archaea[33][34] (Fig. IS200.1 and Fig. IS200.3). Alignment of TnpA from various members shows that they are highly conserved but may carry short C-terminal tails of variable length and sequence. Among approximately 400 entries in ISfinder (December 2023), about 50 examples IS200-like derivatives.

They can occur in relatively high copy number (e.g. >50 copies of IS1541 in Yersinia pestis) and are among the smallest known autonomous IS with lengths generally between 600-700 pb. Some members such as ISW1 (from Wolbachia sp.) or ISPrp13 (from Photobacterium profundum) are even shorter.

IS200 was initially identified as an insertion mutation in the Salmonella typhimurium histidine operon [35]. It is abundant in different Salmonella strains and has now also been identified in a variety of other enterobacteria such as Escherichia, Shigella and Yersinia.

Different enterobacterial IS200 copies have almost identical lengths of between 707 and 711bp. Analysis of the ECOR (E. coli) and SARA (Salmonellae) collections showed that the level of sequence divergence between IS200 copies from these hosts is equivalent to that observed for chromosomally encoded genes from the same taxa[36][37]. This suggests that IS200 was present in the common ancestor of E. coli and Salmonellae.

In spite of their abundance, an enigma of IS200 behavior is its poor contribution to spontaneous mutation in its original Salmonella host: only very rare insertion events have been documented[34]. One reason for these rare insertions could be due to poor expression of the tnpAIS200 gene from a weak promoter pL identified at the left IS end (LE)[38][39] (Fig. IS200.3).

Besides the characteristic major subterminal palindromes [39] presumed binding sites of the transposase at both LE and the right end (RE) (Substrate recognition), IS200 carries also a potential supplementary interior stem-loop structure (Fig. IS200.3). These two structures play a role in regulating IS200 gene expression. The first (perfect palindrome at LE; nts 12–34) overlaps the tnpAIS200 promoter pL, can act as a bi-directional transcription terminator upstream of tnpAIS200 and terminates up to 80% of transcripts[40] (Fig. IS200.3). The second (interior stem-loop; nts 69–138) (Fig. IS200.3), at the RNA level, can repress mRNA translation by sequestration of the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) ((Fig. IS200.3). Experimental data suggested that the stem-loop is formed in vivo and its removal by mutagenesis caused up to a 10 fold increase in protein production[40]. Recent deep sequencing analysis revealed another aspect in post-transcriptional regulation of IS200 expression: A small anti-sense RNA (asRNA) IS200 transposase expression ((Fig. IS200.3) was identified as a substrate of Hfq, an RNA chaperone involved in post-transcriptional regulation in numerous bacteria[41]. Interestingly, asRNA and Hfq independently inhibit IS200 transposase expression: knock-out of both components resulted in a synergistic increase in transposase expression. Moreover, footprint data showed that Hfq binds directly to the 5’ part of the transposase transcript and blocks access to the RBS[42].

In spite of its very low transposition activity, an increase in IS200 copy number was observed during strain storage in stab cultures[35][43]. However, the factors triggering this activity remain unknown[34]. Transient high transposase expression leading to a burst of transposition was proposed to explain the observed high IS200 (>20) copy number in various hosts and in stab cultures [35].

Although regulatory structures similar to that observed in IS200 (Fig. IS200.3) were predicted in IS1541, another member of this group with 85% identity to IS200, this element can be detected in higher copy number (> 50) in Salmonella and Yersinia genomes. However, no detailed analysis of its transposition is available and since no de novo insertions have been experimentally documented and chromosomal copies appear stable in Y. pestis[44], it remains possible that IS1541 also behaves like IS200.

However, the regulatory structures are not systematically present in other IS200 group members and understanding of the control of transposase synthesis requires further study.

The IS605 group

IS605 group members are generally longer (1.6-1.8 kb) due to the presence of a second orf, tnpB in addition to tnpA. Alignment of TnpA copies from this group indicated that although they do not form a separate clade from the IS200 group TnpA, they generally carry the short C-terminal tail. The tnpA and tnpB orfs exhibit various configurations with respect to each other. They may be divergent (Fig. IS200.1 i top: e.g. IS605, IS606) or expressed in the same direction with tnpA upstream of tnpB. In these latter cases, the orfs may be partially overlapping (Fig. IS200.1 ii; e.g. IS608, ISDra2) or separate (Fig. IS200.1 iii; e.g. ISSCpe2, ISEfa4). tnpB is also sometimes associated with another transposase, a member of the S-transposases (e.g. IS607[45][46], see [47]. TnpB was not required for transposition of either IS608 or ISDra2.

Three related IS, IS605, IS606 and IS608 (Fig. IS200.1) have been identified in numerous strains of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori [48][49] . IS605 is involved in genomic rearrangements in various H. pylori isolates[50].

The H. pylori elements transpose in E. coli at detectable frequencies in a standard "mating-out" assay using a derivative of the conjugative F plasmid as a target [48] [49].

The two best characterized members of this family are IS608 and the closely related ISDra2 from Deinococcus radiodurans. Both have overlapping tnpA and tnpB genes (Fig. IS200.1 ii). Like other family members, insertion is sequence-specific: IS608 inserts in a specific orientation with its left end 3’ to the tetranucleotide TTAC both in vivo and in vitro [49] while ISDra2 inserts 3’ to the pentanucleotide TTGAT[53]. Interestingly ISDra2 transposition in its highly radiation resistant Deinococcal host is strongly induced by irradiation[54] (Single strand DNA in vivo). Their detailed transposition pathway has been deciphered by a combination of in vivo studies and in vitro biochemical and structural approaches (Mechanism of IS200/IS605 single strand DNA transposition).

A more detailed and recent analysis of the distribution of 107 IS605 group elements in ISfinder is shown in Fig. IS200.4B [55]. The tree, based on TnpB sequences could be divided into 8 clusters which are overlaid onto the universal tree described by Hug et al., 2016 [56].

The IS1341 group

Elements of the third group, IS1341, are devoid of tnpA and carry only tnpB (Fig. IS200.1 v). The IS occurs in three copies in Thermophilic bacterium PS3[57]. Multiple presumed full-length elements (including tnpA and tnpB) and closely related copies have been identified in other bacteria such as Geobacillus. On the other hand, IS891 from the cyanobacterium Anabaena is present in multiple copies on the chromosome and is thought to be mobile since a copy was observed to have inserted into a plasmid introduced in the strain[58].

Another isolated tnpB-related gene, gipA, present in the Salmonella Gifsy-1 prophage may be a virulence factor since a gipA null mutation compromised Salmonella survival in a Peyer's patch assay[59]. While no mobility function has been suggested for gipA, it is indeed bordered by structures characteristic of IS200/IS605 family ends and closely related to E. coli ISEc42.

In spite of their presence in multiple copies, it is still unclear whether IS1341 group members are autonomous IS or products of IS605 group degradation and require TnpA supplied from a related IS in the same cell for transposition.

IS decay

Circumstantial evidence based on analysis of the ISfinder database suggests that IS carrying both tnpA and tnpB genes may be unstable. Thus, although members of the IS200 group are often present in high copy number in their host genomes, intact full-length IS605 group members are invariably found in low copy number (P. Siguier, unpublished) (See also TnpB). On the other hand, various truncated IS605 group derivatives appear quite frequently.

These forms seem to result from successive internal deletions and retain intact LE and RE copies. Sometimes, as in the case of ISSoc3, orf inactivation appears to have occurred by successive insertion/deletion of short sequences (indels) generating frameshifts and truncated proteins. For some IS (e.g. ISCco1, ISTel2, ISCysp14, ISSoc3) degradation can be precisely reconstituted and each successive step validated by the presence of several identical copies (P. Siguier, unpublished). This suggests that the degradation process is recent and that these derivatives are likely mobilized by TnpA supplied in trans by autonomous copies in the genome.

Among the approximately 400 IS200/IS605 family entries in ISfinder (December 2023), there are more than 200 examples of IS1341-like derivatives. It was suggested that the IS1341-like derivatives might undergo transposition using a resident tnpA gene to supply a Y1 transposase in trans. There is some circumstantial evidence for transposition of IS1341-like elements. For example, IS891, present in multiple copies in the cyanobacterium Anabaena sp. strain M-131 genome [60] was observed to have inserted into a plasmid which had been introduced into the strain and more recently it has been shown experimentally that IS1341 derivatives can be mobilized by a resident tnpA gene [61] (see The IS1341 Conundrum).

ISC: A group of Elements Related to the IS605 Group

Another group of potential IS of similar organisation, the ISC insertion sequence group, was defined by Kapitonov et al.[62] following identification of Cas9 homologues which occur outside the CRISPR structure, so called “stand-alone” homologues. While related to TnpB, they are more similar to Cas9 than to TnpB proteins. These genes were often flanked by short DNA sequences which, like LE and RE of the IS200/IS605 family, were capable of forming secondary structures. Moreover, it was reported that the ends of many ISC derivatives showed significant identity to members of the IS605 derivatives identified by these authors in the same study. (Fig. IS200.25). These structures therefore resemble the IS1341-like group.

These potential transposable elements were called ISC (Insertion Sequences Encoding Cas9; not to be confused with ISCR, IS with Common Region). The name IscB was coined for the Cas9-like protein and IscA for an associated potential transposase protein which was identified in a very limited number of cases. Examples of ISC elements with both iscA and iscB genes are quite rare. Only 7 cases were identified by Kapitonov et al.,[63] (Fig. IS200.26) and only 56 of 2811 iscB examples observed in a more extensive analysis were accompanied by an iscA copy [64] . Most ISC identified were IS1341-like with only the iscB (tnpB-like) gene. These stand-alone IscB copies were identified in multiple copies in a large number of bacterial and archaeal genomes generally in low numbers (<10 copies) although some genomes contained more elevated numbers (e.g. 22 in Methanosarcina lacustris; 25 in Coleofasciculus chthonoplastes PCC 7420; 52 in Ktedonobacter racemifer)[63].

However, in contrast to the observations of Kapitonov et al.,[63] more wide-ranging studies [64] identified rare IscB proteins which were not “stand alone” but were associated with CRISPR arrays (31 examples in a sample of 2811).

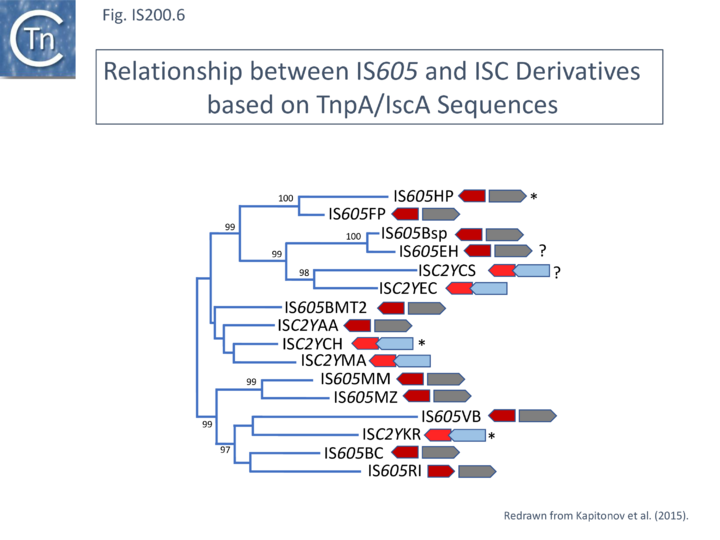

A tree of “full-length” elements (Fig. IS200.26; [63])(i.e. those with both tnpA and tnpB or iscB genes) based on TnpA/IscA sequences showed that full length IS605 and ISC examples carrying both tnpA/iscA and tnpB/iscB are interleaved. IS605 is among those family members with divergent tnpA and tnpB genes (Fig. IS200.1) while other family members carry tnpA upstream of tnpB (e.g. ISDra2). However, in contrast to all IS605-like derivatives, those full length ISC elements included in this tree all have the iscA gene downstream of and slightly overlapping with iscB.

Mechanism of IS200/IS605 single strand DNA transposition

Early models

General transposition pathway

TnpA, Y1 transposases and transposition chemistry

TnpA overall structure

The Single strand Transpososome

Substrate recognition

Cleavage site recognition

Active site assembly and Catalytic activation

Transpososome assembly and stability

Transposition cycle: the trans/cis rotational model

Regulation of single strand transposition

Single strand DNA in vivo

Replication fork

Genome re-assembly after irradiation in Deinococcus radiodurans

Real-time transposition (excision) activity

TnpB and its Relatives

IS200/IS605 and the ISC group

ISC have very similar transposases to those of the IS200/IS605 family and are therefore part of the same super family

TnpB, IscB, Cas12 and Cas9

TnpB and IscB are Related to the RNA-guided nucleases Cas12 and Cas9

IscB and Cas9

TnpB and Cas12

Proposed Evolution of TnpB and IscB from an Ancestral RuvC.

Functional analysis of TnpB and IscB

TnpB functions as an RNA-guided Endonuclease

ncRNAs, sotRNAs and reRNAs

TnpB: mechanism of action

An explanation of the “inhibitory effect reported for TnpB?

A system which functions in Eukaryotes

RNA Nomenclature

Generating re(ω)RNA: Processing

The Structure of TnpB-reRNA in association with DNA

TnpB-re(Ω)RNA: Diversity and Activity

Sequence requirements of the re(Ω)RNA

Exploring and defining TAM sequences in a library extracted from NCBI

re(ω)RNA and tnpB Co-evolution

IscB, like TnpB, also functions as an RNA-guided Endonuclease

The Structure of IscB –ωRNA ribonucleoprotein complex and the ternary complex containing target DNA

The Structure of IsrB–ωRNA ribonucleoprotein complex and the ternary complex containing target DNA

IsrB diversity of structure and ωRNA architecture

The IS1341 Conundrum: how do derivatives without their transposase transpose?

IS1341 Group Diversity: Mining the NCBI NR database

Conserved secondary structure motifs

IS1341 group orientation suggests iscB re(Ω)RNA but not tnpB re(Ω)RNA is expressed in transcriptionally active environments.

IS1341 Group Function

Does a Resident TnpA copy Drive IS1341 group Transposition?

TnpBGst and IscBGst proteins are active RNA-guided Nucleases.

TnpB is Required for Replacement of the Deleted IS Copy.

The Copy Choice Model for TnpB Function During Transposition

IStrons

The IS605-based IStron: CdiIStron.

IS607-based IStrons

TnpAS IS607 Excision and Insertion Activity

IStron-encoded TnpB nucleases

Defining the CBoIStron TAM Sequence: a double role in both nuclease and transposase recognition.

CBoIStron TnpB/wRNA promotes transposon maintenance avoiding transposition-associated transposon loss.

Busy Ends: Functional interactions between IStron splicing, TnpB and ωRNA.

Busy Ends

The Eukaryotic Connection: Fanzor eukaryotic TnpB relatives

TnpB Clade

Fanzor1

Fanzor2 and/or Fanzor1 are of bacterial origin

Fanzor2 and/or Fanzor1 may have evolved from an IS607 ancestor

Fanzor1 may have evolved from Fanzor2

Fanzor Activity

The Functional Relationship Between Fanzor Evolution and IS607 TnpB

Y1 transposase domestication

TnpAREP and REP/BIME

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Fred Dyda and Alison Hickman for advice concerning transposition mechanism, to Orsyla Barabas for certain figures and videos of structures, and to Kira Makarova and Virginijus Šikšnys for advice concerning the RNA guide endonucleases. The Siksnys group also kindly supplied the Cas12 structural panel.

Bibliography

- ↑ <pubmed>6313217</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15179601</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6315530</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>3009825</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9060429</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>15179601</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2546038</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8601470</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7557457</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2553665</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8386127</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9858724</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9858724</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10986230</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10220167</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11807059</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104715</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26350323</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>23832240</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6313217</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9858724</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9631304</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>11807059</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16209952</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>16163392</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18280236</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18243097</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20090938</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20691900</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>20890269</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17347521</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17347521</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10418150</pubmed>

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 <pubmed>15179601</pubmed>

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 <pubmed>6313217</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8253675</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>8384142</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9060429</pubmed>

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 <pubmed>3009825</pubmed>

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 <pubmed>10471738</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>18725932</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26044710</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6315530</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9422611</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10986230</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>24195768</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>26104715</pubmed>

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 <pubmed>9858724</pubmed>

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 <pubmed>11807059</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>9789049</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>37386294</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>27572647</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>14676423</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>17006450</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>37386294</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>27572647</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>7557457</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2553665</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>10913072</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2553665</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>37758954</pubmed>

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 <pubmed>PMC4810608</pubmed>

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 <pubmed>PMC4810608</pubmed>

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 <pubmed>34591643</pubmed>