Transposons families/Tn7 family

Historical

Plasmid R483 was first suspected to carry a trimethoprim and streptomycin resistance transposon because these plasmid determinants became genetically linked to and transferred by a second plasmid, R144, in the host strain [1]. That the two resistance genes were part of a transposable element was confirmed by showing that they could be transposed from the incI→ plasmid, R483, to plasmids of other incompatibility groups such as R391(IncJ), R7K(IncW), and RP4(IncP), which all acquired a DNA segment of about 9 x 106 daltons as judged by sucrose density centrifugation [2]. Remarkably, in contrast to other transposons at the time, transposition into the host E. coli chromosome was also observed to a single locus between dnaA and ilv [2]. The authors pointed out that insertion did not suppress a dnaAts phenotype indicating that it did not involve the entire R483 plasmid. This is because an integrated plasmid was known to suppress dnaAts thermosensitivity by providing an alternative (integrated plasmid-driven) origin of replication for the chromosome [3][4][5], a phenomenon known as integrative suppression [6]. The chromosomally located resistance determinant could undergo subsequent transposition to another plasmid target in a recA independent manner. The transposable resistance determinant was given the name TnC [2] which later became Tn7 [7][8].

The Unique Chromosome insertion site attTn7

The nature of the specific chromosomal insertion site was investigated further [9]: by conjugation, where it was shown to be tightly genetically linked to the chromosomal markers glmS and ilv; by restriction enzyme mapping and hybridization, where it was shown to have integrated into the chromosome at the same unique position in a number of independent “transposants”; and by cloning the chromosome region into a suitable vector plasmid where it was shown that the chromosomal fragment acted as an efficient Tn7 transposition target when cloned in either orientation and, moreover, that Tn7 insertion always occurred in the same orientation with respect to the cloned fragment.

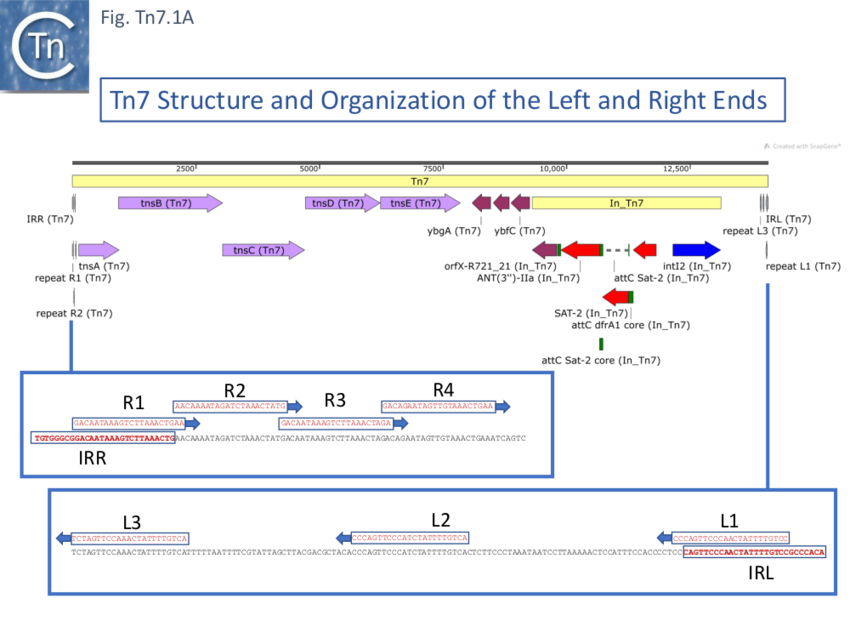

Further analysis of the chromosomal insertion site (which the authors called attTn7 in analogy to bacteriophage attB sites) by DNA sequence analysis [10] identified the junction between the target and each Tn7 end and revealed that insertion created a 5bp direct target repeat and that the ends exhibited short terminal inverted repeats but contained, 22bp repeated sequences over a longer distance which were asymmetric at each end (Fig. Tn7.1A) (see also [11]). These were contiguous in the right end but were separated at the left end [10]. It was suggested that this asymmetry may play a role in the unique insertion orientation of Tn7 in the attachment site. Note that for historical reasons, in contrast to other transposons, the left and right transposon ends are inversed for Tn7. (That is: the end proximal to the transposition genes is labelled Tn7R whereas in most other transposition systems the convention is that the transposase proximal end is defined as IRL). Later studies revealed that 199 bp of Tn7R and 166 bp of Tn7L were sufficient for transposition activity when transposition functions were provided in trans [12].

Insertion Occurs Downtream from glmS in the Terminator

A detailed investigation into the nature of the chromosomal insertion site [13] showed it to be the glmS transcriptional terminator. Tn7 insertion abolishes glmS transcription termination permitting transcription to continue 127 base pairs into Tn7R (Fig. Tn7.1B). This study found several minor differences in the previously described sequence [9] probably due to the technical problems of sequencing at the time. The authors suggested that the insertion provides a coupling between Tn7 transposition and host growth. The IRR end carries a reading frame with showed similarities to the transposases of IS1 and Tn3 and a weak promoter and it was proposed that transcripts from glmS may regulate Tn7 transposase expression by promoter occlusion [13]. It should be noted that while Tn7 insertion inactivates the glmS transcription termination signal, it leaves the glmS gene itself intact. Moreover, it was shown that transcription across attTn7 from the glmS direction, reduces the frequency of insertion [14].

The Insertion site is Conserved in Many Bacterial Species.

Tn7 was initially used quite extensively for transposition mutagenesis and mapping before its organisation and transposition functions had been addressed. These applications included construction of genetic maps of RP4 [15][16] and R91-5 [17] and probing the organisation of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens Ti plasmid [18]. Its use was restricted to plasmids due to its sequence and orientation specific insertion not only into the E.coli chromosome but into chromosomes of other bacteria such as Vibrio [19][20], Pseudomonas [21], Caulobacter [22] or Thiobacillus [23]. However, one report concluded that although Tn7 inserts into a single chromosome locus of Pasteurella multocida, not only does it insert in both orientation but also apparently generates cointegrates [24], an observation which warrants further investigation.

However, although Tn7 inserts principally into attTn7, it was observed to be capable of insertion into other chromosomal sites but at a lower frequency [15][16].

It was also noted throughout these early studies, that Tn7 does not appear to generate cointegrates [25][26] but see [24] and “A switch between cut-and-paste and Replicative Transposition” below.

Tn7 Organization

A Tn7 restriction map [15] placed the drug resistance genes to one side of a unique EcoRI cleavage site and revealed that deletion of some DNA on the other side resulted in a derivative unable to transpose unless complemented by a wildtype Tn7 (see Fig. Tn7.1Ci). Finer deletion mapping generated from a Tn7 derivative with an IS1 insertion [25] defined two segments essential in cis for transposition (the Tn7 ends) (see also [16]), the location of the trimethoprim resistance gene (Tp), the streptomycin/spectinomycin (Sm/Sp) resistance determinant and three regions which contain Tn7 transposition functions (tnp7A, tnp7B and tnp7C) and which cover the Tn7 transposition genes known today (Fig. Tn7.1Cii). Another deletion study [26] observed that two segments, 2.1kb HindIII (fragment D) and 0.9kb BamHI (fragment E) (Fig. Tn7.1Ciii), were essential for transposition but deletions could be complemented in trans, and, moreover, when cloned alone, the HindIII fragment strongly stimulated transposition of another plasmid-carried Tn7. This segment encodes what is now known as TnsE. Additionally, Smith and Jones [17] obtained the DNA sequence of this 2.1kb HindIII fragment and identified an open reading frame encoding a protein of 538 amino acids with a GTG start codon and visualised its protein product. They also identified a second open reading frame which initiated in fragment E and continued into the next segment. This is now known to be TnsC. From the behavior of the two gene products from these two fragments, they suggested that they must interact with each other. Moreover, using appropriate transcription/translation fusions involving the chloramphenicol acetyltransferase and ⬆-galactosidase genes, they identified a promoter located to the left of fragment E and a transcription terminator within fragment F.

Bibliography

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC236151</pubmed>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 <pubmed>PMC236152</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC235447</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC233146</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>781291</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>4927942</pubmed>

- ↑ Lederberg EM. Plasmid reference center registry of transposon (Tn) allocations through July 1981. Gene. 1981;16:59–61.

- ↑ Campbell A, Berg DE, Botstein D, Lederberg EM, Novick RP, Starlinger P, Szybalski W. Nomenclature of transposable elements in prokaryotes. Gene. 1979;5:197–206.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 <pubmed>6276688</pubmed>

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 <pubmed>6283361</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6282401</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2544738</pubmed>

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 <pubmed>PMC1146532</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC94526</pubmed>

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 <pubmed>328901</pubmed>

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 <pubmed>PMC221974</pubmed>

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 <pubmed>PMC216619</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>748948</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC216204</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>2550986</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>6296632</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC220364</pubmed>

- ↑ <pubmed>PMC107274</pubmed>

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 <pubmed>2157128</pubmed>

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Hauer B, Shapiro JA. Control of Tn7 transposition. MolGenGenet. 1984;194:149–158.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 <pubmed>PMC215358</pubmed>